Myth and Metrics: How social media robs us of ritual, and how to revive it

TikTok, Beowulf, and Sacred Repetition

Check out my new conversation with John Vervaeke on his show ‘Voices with Vervaeke’ here. The early-bird period for my course ‘New Ways of Knowing’ runs out in the next 24 hours, find out more here.

Listen! This is how stories used to begin. It is the opening word of Beowulf, the oldest piece of English literature. We don’t know who wrote it, but it almost certainly began as an oral tradition, and it reveals something about storytelling that has never left us. It begins with a call, with a bard asking a crowd to give freely a resource that has always been precious: attention.

Tristan Harris has argued that we now live in an ‘attention economy’, with social networks specifically designed to capture and monetise our awareness. Often, this is done by stoking outrage that keeps us glued to platforms longer. The attention you give online drives ad revenue, determines what TV shows stay on air, and who wins elections. The impact of this on our politics and social cohesion has been the subject of fierce debate in recent years. It’s widely agreed the way social media captures our attention is a significant issue, but what’s spoken of less is what kind of attention it captures.

The bards who told the story of Beowulf, and their counterparts around the world in all times and places, are calling for something in particular when they ask for our attention. Their voice fills the world, and conversations peter out. The crackle of the fire against silence. Every eye is focused, every mind is present. When the storyteller speaks, they pull their words from somewhere beyond themselves; from the traditions and history of the group, and of the land. Let me take you away from here, to somewhere more real. Let me help you remember the stories that connect us, that help us remember who and what we are, and what we owe to this place.

This isn’t the same kind of attention we give to our Instagram and TikTok feeds. It is a ritualised form of intentional presence directed to a shared sense of meaning and history. In The Disappearance of Ritual, the philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that our digital communication sacrifices this kind of deep attention and intensity with something shallow and extensive. Digital communication is defined by how much of it there is, rather than the quality of relatedness it gives us.

As a result, our digital commons has become commoditised and overrun by the cult of self. When we shout ‘listen!’ on social media, we are demanding that others ‘Listen to my story, listen to me.’ This couldn’t be farther from the fireside offering described above, in which our collective attention brings us into contact with a unifying story. Ritual is vital because it gives us a sense that we belong to the world. A sense of connectedness, whether to society, nature or the divine, is in turn linked to a sense of psychological wholeness and lower rates of mental illness.

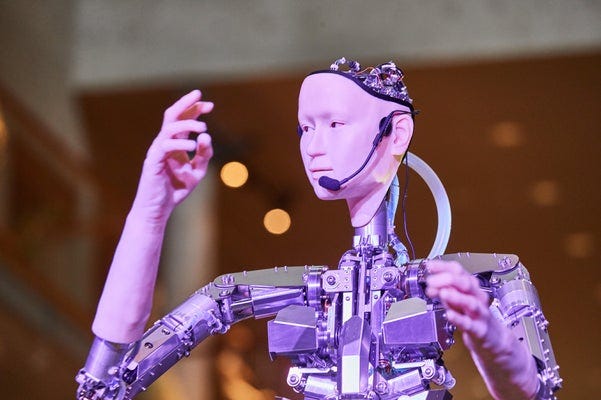

Social media offers the opposite; connection without relatedness. However, our social networks aren’t going anywhere. In fact, the trend is toward more of the same: more time spent online, more immersive tech, more content. Mark Zuckerberg’s Metaverse has, predictably, been a complete failure. But with Apple’s Vision Pro and the growth of AI, we will increasingly see immersive technologies that threaten to deepen our collective disconnection.

We need to revive ritualistic practices and myth-making to feel at home in the world, and to feel bound to a deeper social purpose. Can our social networks ever become places that facilitate this kind of connectedness? Can we reclaim a new kind of ‘deep attention’ online, and what would that look like?

TikTok Troubles

This has been a question I’ve been wrestling with for some time, and particularly over the last few months. Over the summer, I unexpectedly went viral on TikTok with 2.6 million views on my first film. I had mixed feelings about going on the platform; I tried it because my publisher had suggested it would be good for book sales.

In many ways, it’s felt like immersing in a new society and learning a new language. The style of videos is fast, frenetic, colourful. Every few lines needs to be a cliffhanger, jerking attention from all the other videos people could be watching. The quality of content still matters, and people on TikTok are the same as people anywhere, looking for depth and meaning. However, to have your video viewed and picked up by the algorithm, you have to try and grab people in the first few seconds. The result is a twisted inversion of that first call for attention in Beowulf.

Listen! Don’t keep scrolling! I’m going to give you something for you, from me. I’m going to entertain or inform you, and in exchange you will give me your attention. I’m a product, you’re a product, your attention is a product.

TikTok is what happens when Moloch does a hostile takeover of the Tower of Babel. Scrolling through the feed, you’re presented with person after person vying for your attention.

Want to learn how to get gunk off a frying pan with this quick tip? Want to hear my trauma story? Want to see a dog taking care of a baby squirrel? Not into that? How about interior design tips? Ah, you liked that! Check this boho-chic transformation of an Ikea table. Here’s a couple designing a tiny-house. Here’s how to create a lamp out of a seashell.

As the viewer, you are a consumer. As a creator, you are a broadcaster. The two are connected, but not in a truly reciprocal relationship.

The Medium is the Message

There’s a contradiction in me lamenting the ills of TikTok, because I create films there. There are aspects of it I enjoy, and it is for better or worse a new form of human expression. But the question in my mind remains ‘to what end?’ My focus at the moment is to recognise the constraints of the platform and try to find ways to either innovate on it, to see if there’s a way to express more depth than it usually allows for. I could just use it to sell books, but I feel guilty contributing to what is ultimately a meaningless place.

Innovating within an existing platform is always a challenge, because as media theorist Marshall McLuhan argued decades ago, ‘the medium is the message’. TikTok and Twitter/X have short-form content built into the design of the platform, which prevents depth. As I explore in The Bigger Picture, this also leads to what philosopher C. Thi Nguyen calls ‘value capture’ where we have no choice but to express ourselves according to its rules, and sacrifice our own deeper values in the process.

This isn’t true of all digital communication: it depends on the medium. Specifically, whether communication happens in real time, a theme I explored when Clubhouse briefly gained popularity. Video conferencing technology like Zoom can elicit powerful experiences of connection if we use the right practices and intentions in the way we use it. But no digital platform will ever match in-person connection, at least not until they are so intertwined with our sense of embodiment that they become indistinguishable from real life.

However, even if that were to happen, there is a quality of online communication that will always separate it from in-person contact. All digital communication is placeless; everyone watching is doing so from a different physical location. And the idea of being ‘placed’ somewhere, belonging somewhere, is fundamental to human health.

Being Somewhere is Being Someone

To see how this relates to storytelling and myth, we can return to our bard at the fire. What they are doing is retelling or re-enacting a shared myth to bring people closer together. It is a participatory process in which they inviting others into a ritual. As Byung-Chul Han explains,

“We can define rituals as symbolic techniques of making oneself at home in the world. They transform being-in-the-world into a being-at-home. They turn the world into a reliable place. They are to time what a home is to space: they render time habitable. They even make it accessible, like a house. They structure time, furnish it.”

As John Vervaeke has pointed out, this loss of a sense of ‘being at home in the world’ is a key aspect of the meaning crisis. Our social networks provide us with a false sense of timeless connectedness while actually fostering a profound disconnection. We’re connected but can’t connect.

Social feeds lack a sense of time, permanence or place, and so there is nothing to contextualise ourselves against; there’s nothing to belong to. At the same time, social media is strangely intimate, full of feelings and strong emotion, which makes this especially confusing. On social media, people often express themselves in a way that normally we would find from a loved one. We share our deepest traumas. We engage in competitive vulnerability. Perform a game of one-upmanship around who can be more authentic. For Byung-Chul Han, this is the result of the way our communication is captured by neoliberal economics.

Today, we consume not only things themselves but also the emotions that are bound up with things. You cannot consume things endlessly, but emotions you can. Thus, emotions open up a new field of infinite consumption. The emotionalization of commodities and the associated aestheticization of commodities are subject to the compulsion of production. Their function is to increase consumption and production. As a consequence, the aesthetic is colonized by the economic.

As the Gnostics warned us two thousand years ago, when you create a social reality with no connection to a deeper divine essence, and not in alignment to a value greater than itself, you get lost in a maze where essential human values and relationships are mimicked endlessly and blindly in a chaos of hollow repetition. Then, as now, the only way out is to connect to the sacred; to an experience that places us more fully in reality.

No Time for Time

Deeping our connection to reality involves placing ourselves both in time and place. The religious historian Mircea Eliade argued that reframing time is one of the key aspects of myth. His concept of ‘eternal return’ suggests that myth plays a consistent role in religions and cultures around the world by allowing us to go beyond the profane - our day to day reality and all its confusion, delusions and tangles - and return to a ‘mythical age’ beyond time.

That ‘mythical age’ is the sacred, the heart of what matters most and what ultimately created everything else. This return can happen through enacting a myth, but also through the telling of it. Real myth brings us into ‘sacred time’ that both transcends and permeates our day to day lives. For example, the Aboriginal Australian Dreamtime isn’t just a story, or a creation myth; it’s an access point to a truer reality that contextualises and defines this reality.

Social media inverts this entirely. There is no sense of permanence, place or time. It is located briefly in your phone or computer, but ultimately it’s ‘in the cloud’. Ephemeral, disconnected, open-ended. As Byung-Chul Han argues,

The neoliberal regime…intentionally abolishes duration in order to drive more consumption. The permanent process of updating, which has now extended to all areas of life, does not permit the development of any duration or allow for any completion. The everpresent compulsion of production leads to a de-housing [Enthausung], making life more contingent, transient and unstable. But dwelling requires duration.

In short, you can’t inhabit a social network, no matter how much time you spend online. You will always be ‘de-housed’, adrift, alone. On the other side, myth and ritual are always linked to place in some way. In many cultures, myths are understood to be given by the land, not made up by people. They often foster a deep connection to the land, and a renewal of a deep relationship that the community has with where they live. Traditionally, myth and story has been one of the most important ways people gain a sense of ‘being at home in the world’ that we now know is so crucial to our psychological well being. And fundamental to this is the kind of attention it requires: a deep, abiding presence. For Byung-Chul Han,

The cultural technique of deep attention emerged precisely out of ritual and religious practices…Every religious practice is an exercise in attention. A temple is a place of the highest degree of attention. According to Malebranche, attention is the natural prayer of the soul. Today, the soul does not pray. It is permanently producing itself….Digital communication channels are filled with echo chambers in which the voices we hear are mainly our own. Likes, friends and followers do not provide us with resonance; they only strengthen the echoes of the self.

Online, we are lost in a sea of ourselves. A sea that goes on and on, without apparent purpose. In this way, social media has co-opted another aspect of our shared humanity.

The Return of Repetition

In The Disappearance of Ritual, Byung-Chul Han explains that “Rituals are characterized by repetition. Repetition differs from routine in its capacity to create intensity.”

Rituals involve enacting reality; tapping into the imaginal, the place between our minds and the world, to take on new and wider perspectives. We can do this by revisiting, over and over, particular gestures, stories, practices and techniques to deepen our relatedness. The realms of TikTok and Instagram are designed not to revisit and repeat the old, but to continuously produce the new. What defines them more than anything is their insatiable hunger for content. Any return to the old is done ironically, or for a new audience who hasn’t seen it before. It’s ‘retro’, but not ‘rooted’.

Social media gives us addictive routine; constantly checking our phones, mindlessly scrolling, endlessly searching for new stimulation. In this way, it keeps us trapped in profane time. Endless cycles without much substance, a timelessness that isn’t full, but empty. Look up from a social media feed and you may have lost half an hour, but that half an hour wasn’t spent in an ‘eternal return’ to the sacred. It might have been spent watching cat videos, instead of relating deeply to others, yourself or the world.

The one exception is this film, which is guaranteed to bring you into an eternal return with the sacred.

Conversely, intentional repetition aimed at connecting to something beyond our current perspective can bring us into deep attention. Wisdom traditions around the world use repetition in this way. Mantras are a famous example, as are ritualised dances, rubbing rosary beads, or going on pilgrimage.

Considering this gave me a new lens on my own unhealthy social media habits, and on one of my hobbies, playing traditional Irish music. This year marks 20 years of since I started playing the Irish flute, so my relationship to it has been on my mind, and I’ve been wondering what it was that drew me to it and kept me devoted to playing.

Irish music is formal and repetitive; we don’t really improvise, and to play along with others you have to know the tunes. People do write new tunes, and these make it into the collective repertoire, but these are few; there is an implicit understanding that this is a traditional art form. A session, where musicians gather to play (almost always in a pub) is a ritual with unspoken norms and etiquettes that you just have to know. It values collective over individual expression, and it is full of repetition. There are tunes I have played thousands of times and still enjoy.

But the form and etiquette isn’t the main pull for me. The main pull is the exact opposite of my feeling of guilt at how much time I spend on social media; when I play, I go somewhere else that matters. Somewhere beyond myself that I feel inexplicably connected to.

Music can be a powerful carrier of sacred time; whether in a gospel choir or an Irish session. It takes us somewhere else, somewhere both interwoven with this reality and beyond it. If we can bring those kinds of forms and practices into our social networks, could the internet become a place of true connection, instead of the false mimicry it is today?

Conclusions

The social networks we have today, and the kind of culture they form, are so far removed from the practices that embed us in the world that it can be hard to see them as beneficial to the soul. However, social networks are still populated by human beings, and we are all looking for ways to connect to something greater. Setting aside the mental health problems social media is contributing to among younger people, research suggests that the majority of us aren’t actually enjoying our existing social networks all that much.

A 2021 study revealed that nearly two-thirds of people surveyed believed life was better before social-media platforms, and 42 percent of Gen Z respondents said they felt addicted to social media and couldn’t stop if they tried, even though ‘depressed,’ ‘angry,’ and ‘alone’ were the most common words they associated with Facebook, while ‘missing out’ and ‘alone’ were the words most commonly associated with Instagram.

This points to a colossal rift, and a deep desire. The place we go to connect, tell stories and participate in the social fabric is actively preventing us from accessing deeper, more intensive forms of experience that give us a sense of place and safety in the world. But we still deeply desire those deeper experiences of connection.

There are a lot of potential responses to this, ranging from unplugging completely to trying to design new social networks centered on wisdom and deep human connection. Maybe the least likely seems to be transforming our existing platforms so that they meet our deeper needs. Bringing embodied and enacted ritualistic myth-making into TikTok, Instagram and Twitter/X seems outlandish when we look at how those platforms are built, and what they’re incentivised to do. Change would have to be made at a deep structural level, including the algorithms and corporate policy. Seeing as these are both subject to market forces, which don’t value things like ‘sacred time’ or ‘people feeling at home in the world’, it’s unlikely.

The second option might be more achievable; to engage in collective practices that bring us into ‘deep attention’ in our lives to counter the hollowness of our digital worlds. Online, this can likely only happen in real-time forms of communication. In-person, it can be hard to find places where we can engage in embodied practices and ritual processes that move us toward an ‘eternal return’, but they are out there. Regardless of where we find that connectedness, what seems important is to have a balance in our lives, where for every hour we spend with shallow attention online or binge-watching a show, we counter it with an hour or more of deep attention. In prayer, in connection, or any mind-states or rituals that bring us into a collective appreciation of the sacred.

What remains most hopeful for me is the idea that, eventually, we can turn at least some of our digital commons into a place of ritual connection and deep attention. It may be that we’re facing a situation that requires a forward escape; that asks us to draw up myths from the roots of our humanity and force them into our digital worlds with a loud cry of ‘Listen!’

Well, that was a chock full package and maybe everyone is still reeling trying to take it all in. Let me add to the idea of story: "For example, the Aboriginal Australian Dreamtime isn’t just a story, or a creation myth; it’s an access point to a truer reality that contextualizes and defines this reality." Love your links and here's one for you to add: "Everything will change if we adopt the Universe Story": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUEu4YT0ZSA

>As the Gnostics warned us two thousand years ago, when you create a social reality with no connection to a deeper divine essence, and not alignment to a value greater than itself, you get lost in a maze where essential human values and relationships are mimicked endlessly and blindly in a chaos of hollow repetition. Then, as now, the only way out is to connect to the sacred; to an experience that places us more fully in reality.

Curious about this topic - where do the gnostics write about this? Is there a specific text you can link?