Intelligence comes in many forms, and in many guises we don’t understand. One of the most fascinating is fungi. Neither plant nor animal, fungi have more in common with us genetically than we do with plants. They make up the most populous kingdom on the planet, with an estimated 3.8 million species, 90% of which remain undiscovered.

You can’t see most of it. It exists as mycelial networks underground that can spread for thousands of acres, exchanging nutrients, information and more to help whole ecosystems survive. Fungi was nature’s Internet millions of years before the first humans discovered fire, and we wouldn’t be alive without it. It can feed us, heal us, poison us, and clean up toxic waste. Some species, like psilocybin mushrooms, can elicit profound mystical experiences.

Few people know more about fungi than Paul Stamets, who is probably the most famous mycologist in the world. He’s the author of six books, including Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World, the star of the documentary Fantastic Fungi, and even has a Star Trek character named after him. He’s also coming to speak at Breaking Convention in April, Europe’s largest conference on psychedelic science and culture (of which I’m a co-director), so I caught up with him ahead of the conference to get his thoughts on how mushrooms can help save the world.

Usually when I put out an interview, I weave together the interviewee’s answers with themes I’ve been exploring on The Bigger Picture. Transcribing this one, I realised I didn’t need to. So much of what Stamets reveals about fungi applies to themes I’ve written about recently, from the nature of complex adaptive systems, the importance of resilience, why we need heterodox thinking, the consciousness of Artificial Intelligence and the need for the re-emergence of the sacred in society.

Paid subscribers get early access to the full video interview with Stamets before we release it on the Breaking Convention YouTube page, as well as a growing archive and 10% off the upcoming Art of Difficult Conversations course.

Without further ado, let’s dive down into the wonderful world of fungi.

Alexander Beiner: Paul Stamets, welcome. We're really thrilled to have you joining us at Breaking Convention this year.

Paul Stamets: Honoured to be here, Alexander, good to see you again.

Alexander Beiner: I wanted to start off by asking, what are the most personal lessons you’ve gained studying fungi?

Paul Stamets: Mushrooms, fungi and mycelium have deep philosophical implications, as well as practical implications. I love the marriage of the idealistic and the practical coming together, because that way we can have effective change for the better. In the many years that I've been studying mushrooms, what really dawned on me, particularly while using the scanning electron microscope to look at mycelium, is its network-like design.

Also, how mycelium often benefits from disturbance. Very few organisms benefit from disturbance. Due to epigenesis, [after it’s disturbed], the mycelium grows out at the end [as part of its recovery]. The mycelium [grows] literally millions of end-tips in a cubic centimeter that then encounter new food, toxins, new opportunities, new challenges. It's like having little scientific teams at the end of every little tip of mycelium that are working together to see if they can come up with a solution. And then, out of the millions and millions of experimental teams in these tips, one or several may be successful.

And what happens then, if they are successful, is that they surge and they grow. But what's extraordinary, because they're a network-like design, is that the information gets back-channeled into the genome of the species and becomes the part of the “resonant body intellect,” if you will, of the mycelium. So now it's become educated. If it meets another pathogen, a bacterium, a virus, a toxin, it can upregulate the gene sequences and the proteins that allow it to overcome that obstacle.

So it really speaks metaphorically to something I think is very, very true: that our biodiversity is formed by the minority that leaves evolution. And so it's really important that we protect the minorities in our society. Scientific innovation does not come from the majority. It comes from surges of individuals who are up against conventional wisdom, breaking convention. These people surge with an idea that seems radical or preposterous to some, and in fact seems preposterous to most, but they can be right. And when these individuals are right, at the cost of being ridiculed, at the cost of failure (and most of them do fail), we then have innovation that is paradigm shifting. Mushrooms are a bridge across cultures, across continents, across the centuries, bringing in indigenous and minority cultures that have been using mushrooms and sharing their knowledge.

The lesson of psilocybin [the active ingredient in magic mushrooms] is that you want to share it. You don't want to keep it to yourself. In fact, those who want to control these medicines are antithetical to the whole message that psilocybin gives, which is that we can be better people together. We are all one. We are one with the planet, we're one with the universe. And so I'm so excited that there's an awakening, literally a revolution from the underground that's now surging all over the world.

And as these mycelial networks combine, and as these cultural networks combine, we’re sharing knowledge. And so whether it’s the Eleusinian mysteries in Greece, or the use of magic mushrooms in Mesoamerica, it is logical that every culture that has these psilocybin mushrooms in their ecosystem will eventually discover them.

But think about this: mushrooms come up and disappear in four or five days. So they're ephemeral. Some mushrooms can feed you, some can kill you, some can heal you, some take you on a spiritual journey. But you have to wonder, like, what was that? Something that came up one time, you know, and then disappeared. Whereas plants and animals are in your horizon of your experience for years, decades. You have a familiarity factor because of constant contact. With mushrooms, it's intermittent contact, but the contact is so profound and life changing that it's the experts within those cultures that become knowledgeable about how to safely collect them and use them.

And again, those are the minorities. It's the minorities within cultures that are the knowledge keepers. And thankfully, because of our ability now of the Internet, which I believe is also based on a mycelial-like design (inevitably we create and recreate the structures that have been successful biologically) we have resiliency now and we have shared knowledge. And so those of us who have voices for these fungal allies that have seemed to be on the fringes, are now becoming more mainstream because people know that collectively mycelium and mushrooms bring us together and make us stronger. And, I believe psilocybin makes us into nicer people.

Alexander Beiner: Amen to that. There are a few things I want to pick up on, starting with the point you made about the structure of the Internet. This is something I've thought about a lot recently - right now, we're in this very interesting time where we're asking whether these AI chatbots - which Google and Microsoft have put a lot of money behind - are conscious [see my recent piece about this here]. I guess the same question also applies to a mycelial network. You talked about mycelium gathering information, remembering in some sense applying knowledge and adapting to change. Would you define a mycelial network as conscious in the way that, say, human being is conscious?

Paul Stamets: Well, I think we're limited by our language skills, and our misunderstanding, or poor understanding, of natural systems. I saw a report that said there can be up to a thousand species of bacteria in a single gram of soil. But there can be up to eight miles of mycelium in a cubic inch of soil. The mycelium produces antibiotics and probiotics that selectively invite or repel allies or enemies (pathogens). They set up these ‘guilds’ of communities, and the interrelationships are so incredibly complex. We have a thousand species of bacteria up-regulating proteins, which are all having molecular handshakes with each other. They build these ‘guilds’ of enormous complexity.

So, as excited as we are about ChatGPT, I think the mycelium and nature and the soil microbiome have far greater depth and immediacy of use. And this is the thing - ChatGPT can create an alternative reality, but it is an alternative reality. It is not the reality that gives us birth. It’s an intellectual fantasy play, which is extraordinarily interesting and entertaining, and also extraordinarily useful and extraordinarily dangerous. But ultimately, you cannot eat ChatGPT. You can eat a mushroom.

I love ChatGPT, but I'm going to bet on Mother Earth. I'm going to bet on soil. And I have a keen sense, and I think all of us do, that there’s a wealth of knowledge literally underneath every footstep that we take, we barely have the tiniest understanding compared the potential of this design that's evolved over billions of years that we can then improve upon. We can then select out these scientific discoveries the mycelium has made that have applications now. The crisis that we face is in the immediacy of now, with climate change, with our political divides or our religious divides. There is nothing that brings us together more than mycelium and psilocybin mushrooms and medicinal mushrooms and food mushrooms. It checks every box.

Alexander Beiner: I want to talk a little bit about that specifically, because it's always felt fairly miraculous to me, that psilocybin exists to begin with, because my own journeys with it and lessons have been so life changing. It's hard for me to conceive of my life without psilocybin. Why do certain mushroom species produce it? I guess there's a lot of lenses we can look at this through, for example from an evolutionary perspective or maybe from the mycelial perspective, but put simply, what do you think is the purpose of it?

Paul Stamets: This is kind of a favourite subject of mine. So, I respect all my fellow researchers and people do criticise me, so I'm going to reserve and tone down my own criticism. But I am a little bit exasperated when a group of scientists publish a paper saying psilocybin is an insecticide. Alexander Shulgin, the great scientist [and psychedelic chemist] worked for Dow Chemical. He was looking at tryptamines initially to weaponize them against insects, as insecticides, because they interfere with neurotransmission. So the idea is if you interfere with neurotransmission, you can kill the insect.

But unfortunately, of course, those insecticides are damaging to our nervous system as well. So, some great scientists wrote a position paper saying psilocybin likely evolved to be an effective insecticide. I wrote one of the authors saying, “Interesting paper. I love your theory. Have you ever collected psilocybe cubensis mushrooms in the wild? And did you know that every specimen of psilocybe cubensis that I have harvested has had fly larvae growing in the mushrooms? If they evolve to be an insecticide, it’s a very poor insecticide. To their credit, one of the scientists wrote back saying, “oh, my gosh, no, I did not know this.”

So when you have a separation of academia from the natural world, you can make fundamental mistakes. Now, they could be right. It could be a selective insecticide, maybe selective in choosing the insects, the larvae and the flies that are hatched that can help propel the species by spreading a spore. So as much as my reaction is, “Oh my gosh, these scientists did not have real world experience”, there could be a thread of truth here. This is where I'm going to pause on my skepticism and say, “Well, there could be a selective influence on the species of insects that it has chosen to allow to use it as a host platform for spreading their progeny.” But as of yet, we don't know that.

So why do some mushrooms produce psilocybin? Psilocybin is structurally very, very similar to serotonin and the tryptamine pathways are found throughout nature. I like to challenge people with a thought experiment. Look outside right now. I'm in a beautiful place on a remote island in British Columbia. I see all these trees and all these different plants all around me. Strip away all the cellulose, all the lignin, all the heavy cellulose, the structure, everything except for tryptamines. What would you see? You will see the exact same thing you're seeing right now. If all you saw was tryptamines and nature, you would see the trees, the grass, you’d see everything. So the question, I think, is broader than why is psilocybin being produced in mushrooms? I would say why are tryptamines so universal throughout the fungal and the plant in the animal kingdoms?

Psilocybin is just one elaboration from a large well of tryptamines that is the common thread that brings all life together, at least on land. And now we know in sponges and elsewhere in the ocean, so it just keeps on getting bigger and bigger. The tryptamine pathways in nature, I think, are part of the universal construct that links us all together. Psilocybin is one elaboration.

And of course, it excites humans, and humans cultivate those mushrooms. The mushrooms have found a successful new vector and partner to help them propagate. It becomes a little bit like circular reasoning, you know [a question of] the chicken or the egg, but the point is psilocybin mushrooms now have a better chance of survival because of human engagement.

The knowledge of psilocybin mushrooms protects them, whereas prior to that, the devastation of ecosystems holding these species meant we could have lost them. I grew up in a charismatic Christian family, (I’m not of that ilk now) and I was always amused and saddened by this idea of Christianity being opposed to evolution.

So I created a bumper sticker: Evolution is God's Intelligent Design for my car. I got harassed on the freeway all the time. I had a Christian van come up to me, and the guy was yelling at me, “We're going to pray for you.” I said, “OK, I'll pray for you too, see you later!”

But evolution is a design of nature in order for us to literally become better. Collaboration is much better than conflict. Collaboration is sustainable. Conflict is not. Conflict is truly short term gains at long term expense. Cooperation has long term benefits for the commons and is more sustainable. And frankly, it's more spiritually aligned with most all of us. I fundamentally think people are good. I think that exploitation, domination, persecution of people for their religious beliefs, these are wounds that our cultures and our societies have endured that creates generational abuse, people often repeat the abuses that they've suffered. They passed on that abusive behaviour oftentimes, not always, but this is where mushrooms could be a remedy in breaking that generational chain of violence and exploitation, to help people better endure.

Paul Stamets will join Amanda Feilding, Graham Hancock, Maria Papaspyrou, Erik Davis, Carl Hart, Jonathan Ott and dozens of other brilliant scientists, philosophers, clinicians and artists giving talks, workshops and installations at Breaking Convention on April 20-22 at the University of Exeter.

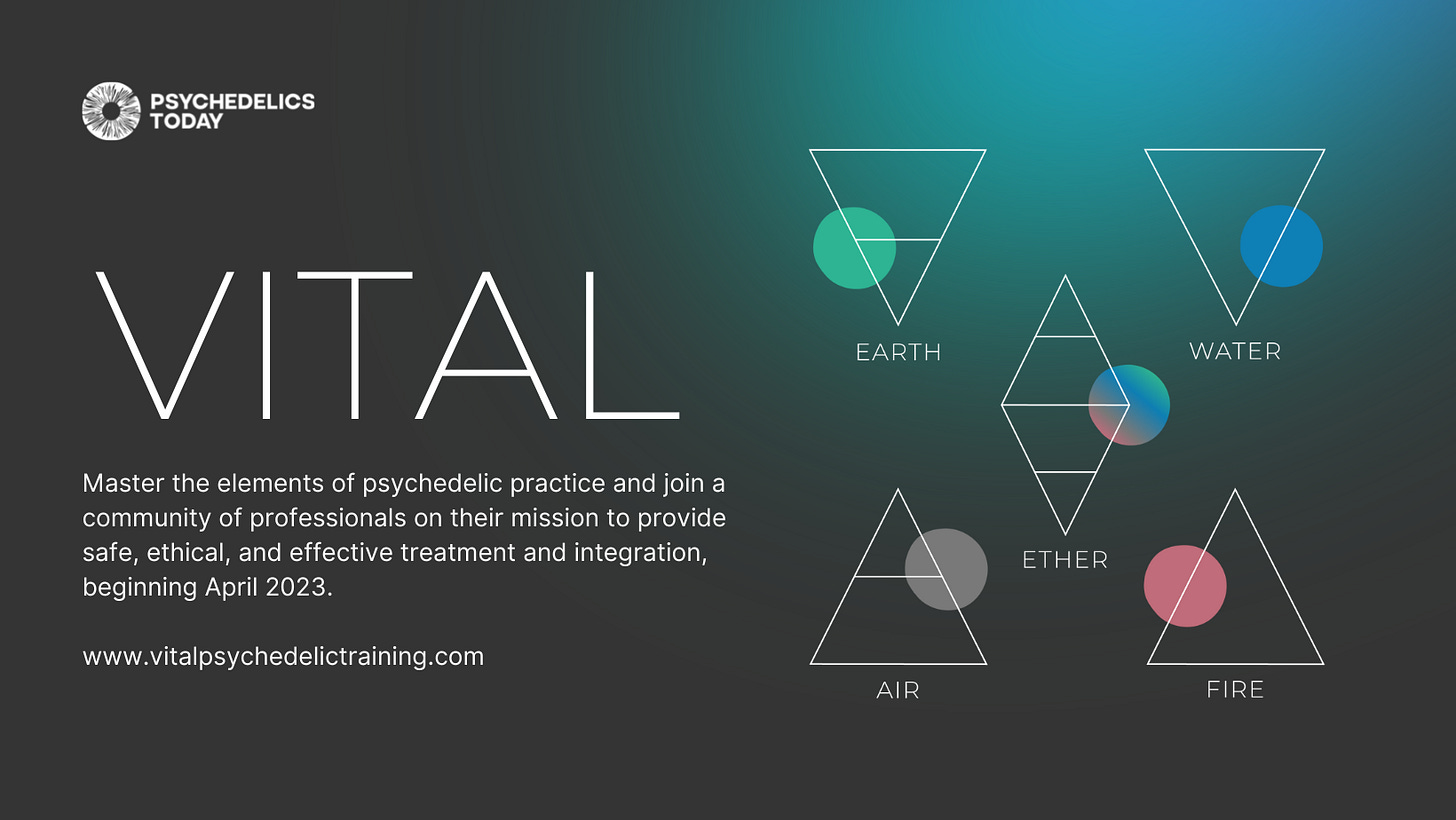

This year, Breaking Convention is partnering up with Psychedelics Today, who have launched their second cohort of Vital, a 12-month psychedelic certificate training program for professionals to master the elements of psychedelic-informed therapy and integration, beginning April 17, 2023.

Designed by trusted leaders in education, Psychedelics Today, and taught by over 35 industry pioneers in a digital environment, Vital bridges academic, clinical, philosophical and reflective approaches to healing. The program features experiential retreats and offers flexible payment plans with diversity and equity scholarships available. No prerequisites required.

There are a lot of psychedelic training courses out there right now, and this is one of the ones I’d personally recommend having heard peoples’ feedback from the first cohort. Click the button below to find out more.

Thanks for reading and subscribing. I’m currently working on a couple of features and a scene comparison of The Last of Us show and game as a follow up to my piece on masculinity in media, so keep an eye on your inbox in the next couple of weeks.

Stamets! What a legend. Great interview

Extremely interesting and thank you both.