Reality Eats Culture For Breakfast: AI, Existential Risk and Ethical Tech

Why calls for ethical technology are missing something crucial

A Leviathan is stirring in the depths. On the surface, those who called it into being are reeling in their nets, terrified it will pull them down. Our Leviathan is artificial intelligence. Our hapless fishermen are the growing number of technologists, ethicists and sociologists calling for a halt in research as Microsoft and Google face off in a new AI arms race.

Elon Musk recently signed an open letter calling for a six month halt in giant AI experiments. Soon after, AI luminary Eliezer Yudkowsky called for a complete halt to all research. Just before that, Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin gave a talk at the Center for Humane Technology arguing that we’ve passed a turning point with AI, and urgently need to consider the ethics and values with which we’re designing it.

The prospect of runaway AI encapsulates two important aspects of the metacrisis we face at this time in history. Firstly, our technology is outpacing our cognitive, moral and spiritual capacities. Secondly, we don’t have a cultural or scientific story to explain consciousness, or the experience of being alive, that makes any sense.

This is a piece about how these two tensions are deeply linked, and what we can find by unraveling them. It’s about why appealing for value-driven technology is a losing battle unless it includes a radical revisioning of our ideas about what reality is to begin with. I’ll explore what the conversation around AI reveals about the broken foundations of high-tech democracies, and why a radical new view could fundamentally change not just how we construct our technology, but society as a whole.

But before all that, I have some important points to make about fish farming.

Above the Depths

You own a fish farm. The strange events in your life that led you to owning a fish farm aren’t important right now. What’s important is farming as many fish as possible. Your farm is on the edge of a pristine lake, and there are nine other farms dotted around the shore. Sometimes you drink your coffee in the morning, look out over the glistening water and watch your competitors. Business isn’t great, and you’re trying to figure out what to do about it. You have bills to pay, a family to support, and above all, fish to farm.

One of the biggest costs you have is the maintenance of a filter that prevents effluent from leaving your farm and entering the lake. Every farm has to use a similar filter by law, and regulators come round to check once a month. One day, you accidentally discover that there’s a way to turn off your filter without the regulators noticing. That would save you a lot of money. At first, you leave it on. After all, turning it off would cause effluent from your farm to spill into the lake and you don’t want that to happen. What kind of example would you be setting for your children? But times are tough. Inflation, taxes, your kid’s college fund all start to mount up. It’s all too much and you’re struggling. Eventually, you’re faced with the choice to turn off the filter or watch your fish farm tank.

With a gnawing guilt, you turn it off. The regulators don’t notice. Profits climb, then soar. Pretty soon, you have enough money to buy your neighbour’s fish farm. Across the lake, the other farmers watch you over their coffee and wonder how you’re doing it. Then one of them figures it out. She can either turn you in, or she can turn her filter off and reap the same profits. She does, and eventually she’s able to buy her neighbour’s farms too.

Months later, the two of you own all the fish farms around the lake. With no filters running, the lake is filled with effluent. Chemicals choke the birds. The stench becomes unbearable. The water quality gets so bad that eventually all the farms fail. Taking your profits, you both go out in search of a new lake.

Moloch The Machine God

Google and Microsoft are in an arms race to create something that could not only destroy the information commons, but potentially all of humanity. Both they and the fish farmers are caught in what’s called a multi-polar trap. A race-to-the bottom situation in which, even though individual actors might have the best of intentions, the incentive structures mean that everyone ends up worse off, and the commons is damaged or destroyed in the process. In his seminal essay ‘Meditations on Moloch’, Scott Alexander personified this universal conundrum in our society as ‘Moloch’, and used the example of a fish farm to bring it to life. Moloch was a Canaanite god of war, a god people sacrificed their children to for material success. I’ve written about Moloch several times before, and I think Liv Boeree’s explanation from a piece I wrote about psychedelic capitalism is one of the best I’ve heard:

If there’s a force that’s driving us toward greater complexity, there seems to be an opposing force, a force of destruction that uses competition for ill. The way I see it, Moloch is the god of unhealthy competition, of negative sum games.

Understanding Moloch is crucial for understanding what we’re facing with Artificial Intelligence. Firstly, it reminds us that all AI research is embedded in a socio-economic system that is divorced from anything deeper than winning its own game. We might call on a halt to research, or ask for coordination around ethics, but it’s a tall order. It just takes one actor not to play (to not turn off their metaphorical fish filter), and everyone else is forced into the multi-polar trap.

In a recent article in Time, one of the founding thinkers of modern AI, Eliezer Yudkowsky, argues that the 6 month pause on AI research proposed by Musk and others is not nearly enough. Instead, he thinks we need to shut down all AI research immediately because of the potential dangers it poses. He points out that even if some actors stopped research, or a wide-spread ethical framework could be implemented, it won’t solve the problem:

Many researchers working on these systems think that we’re plunging toward a catastrophe, with more of them daring to say it in private than in public; but they think that they can’t unilaterally stop the forward plunge, that others will go on even if they personally quit their jobs. And so they all think they might as well keep going.

Yudkowsky’s key point is that, until we have the capacity to design AI to ensure it actually cares about people, we shouldn’t be researching it any further. He writes:

Without that precision and preparation, the most likely outcome is AI that does not do what we want, and does not care for us nor for sentient life in general. That kind of caring is something that could in principle be imbued into an AI but we are not ready and do not currently know how.

Yodkowsky is suggesting that a care for sentient life is something we could imbue into AI if we knew how. I think the sentiment is revealing of a much deeper dynamic. In the cultural story of secular, technologically advanced democracies, human life is valued from a humanistic standpoint. That is, from a belief that we don’t need a higher power to be ethical. We have the capability, and the responsibility, to lead ethical lives of personal fulfilment that aspire to the greater good. This is a prevalent view in the scientific and tech worlds.

To see why a humanistic stance isn’t enough to create ethical technology, let’s imagine for a moment that Moloch is more than just a metaphor. Instead, it’s an unseen force, an emergent property of the complex system we create between all our interactions as human beings. Those interactions are driven by behaviors, memes, ideas and cultural values which are all based on what we think is real and what we feel is important.

AI researchers are calling on one another to find a higher value than growth and technological advancement, but they are usually drawing those values from the very same humanistic perspectives that built the tech to begin with. It is of limited effectiveness to appeal to ethics in a socio-economic system that values growth over all things. Deep down we probably know this, which is why our nightmarish fantasies about the future of AI look very much like a manifestation of Moloch. A new god that cares nothing for us. A gnostic demon that has no connection to anything higher than domination of all life. A mad deity, that much like late stage capitalism, can see nothing beyond consumption.

In Meditations on Moloch, Scott Alexander states that ‘only another God can kill Moloch’. Which begs the question, where might we find that god today? Another way to put this is, “what could we appeal to that is so strong, so compelling that it spurs the kind of collective action and coordination needed to tackle the dangers of exponential technology?”

Another option is that we don’t. We set aside, for a moment, the question of what values we should build into tech, or what values we should appeal to in order to halt its disastrous progress. In fact, we forget about values and ethics entirely.

Why Values Are Bunk

You look out across the lake, watching the trails of gray effluent seeping from the fish farms you and your competitor now own. You could give it all up, and somewhere deep down in your guts you feel this is the right thing to do. But you have kids to feed. Will you risk their future too? You feel trapped. In times past, you may have done something that today feels antiquated. Got down on your knees, opened your heart and asked for guidance from something beyond you. God. The spirit of the lake. Your ancestors. Today, there’s no way out but through more growth. So you check your phone and get ready for a day farming fish.

The issue at play in the AI question, or the question of tempering our growth in general, isn’t just that our technology is built without higher values that can mitigate its excesses. It’s that culturally we lack a story as to why values even matter to begin with.

It’s futile to appeal to ethics in this context, because the ethics aren’t embedded at a deep enough level to counter powerful incentive structures. They aren’t worth dying for, because the system doesn’t value them, it only values quantity. More happiness, more things, more growth, more justice. Tech companies are embedded within, and contribute to, a narcissistic, addicted culture that can only ask for more.

There is a famous thought experiment used in AI circles called ‘The Paperclip Maximiser’. Devised by philosopher Nick Bostrom, it’s a thought-experiment designed to show that even AI imbued with seemingly innocuous values or tasks can be catastrophic. As Bostrom describes it:

Suppose we have an AI whose only goal is to make as many paper clips as possible. The AI will realize quickly that it would be much better if there were no humans because humans might decide to switch it off. Because if humans do so, there would be fewer paper clips. Also, human bodies contain a lot of atoms that could be made into paper clips. The future that the AI would be trying to gear towards would be one in which there were a lot of paper clips but no humans.

This is the kind of apocalyptic scenario Yudkowsky (and many sci-fi writers) are imagining, and he’s probably right to do so as things stand. AI designed by a hyper-individualist consumer culture will likely look something like the Paperclip Maximiser, blind to anything but growth, and any values or ethics will be secondary to this because they are secondary to the culture that built it.

Another possibility is that tech companies do earnestly try to imbue strong values into the design of AI, but that these are ultimately so shallow and contradictory that they result in some other version of the Paperclip Maximiser. In technological consumer cultures, values are exchangeable commodities. This is partly why identity has become a religion in the internet age: it’s fluid, exchangeable, malleable. You can buy new accessories for it. You can make it your own. Freedom, or self-expression, or justice, these are lifestyle choices that don’t exist beyond the individual.

Real virtue comes not from performative values, but from an alignment with a deeper level of reality. Or, as Lao Tzu puts it, “The highest virtue is not virtuous and that is why it is virtuous.” In his excellent piece on Tolkein and C.S. Lewis, N.S. Lyons describes how both thinkers saw the seeds of our growing tech dystopia. And part of it, according to C.S Lewis, came from a misunderstanding of where values come from. Lewis wrote that “The human mind has no more power of inventing a new value than of imagining a new primary colour.”

Values, in the way C.S Lewis and theologians might define them, come from an alignment with true reality. They are not commodities for us to trade in a narcissistic quest for self-fulfillment, or things we can make up, choose from a pile and build into our technology.

From this perspective, real values come from beyond humans. From the divine. They are not something that can be quantified into ones and zeroes, but something that can be felt. Something that has quality.

How we got here

Quality is probably the most important concept in this piece - but what it has to to do with AI isn’t immediately obvious. To see why it matters, we can look at the role an orientation toward quality plays, or doesn’t, in the metaphysical foundations of the West.

Let’s return to the lake, press rewind and go back in time. The farms vanish. Forest erupts on the shore. The jetty disappears. The sun rises and falls, rises and falls. Stop. We’ve reached the late 1600s, and the beginning of the cultural conditions that led to AI. It was between now and the early 1800’s that the Age of Enlightenment would radically change the world.

It was during this time that the things we take for granted now in the West – individual liberty, reasoned debate, and the scientific method – began to take shape. Our science, philosophy and conception of reality is still heavily influenced by Enlightenment thinking – specifically, by a French philosopher and mathematician named René Descartes. In the mid-1600s, Descartes sowed the intellectual seeds that would radically change how we view ourselves, our minds and matter. As John Vervaeke explains in Awakening from the Meaning Crisis:

[Descartes’] whole proposal is that we can render everything into equations, and that if we mathematically manipulate those abstract symbolic propositions, we can compute reality. Descartes saw in that a method for how we could achieve certainty, and that he understood the anxiety of his time as being provoked by a lack of certainty and the search for it, and this method of making the mind computational in nature would alleviate the anxiety that was prevalent at the time.

Just as we are living through the anxiety of the metacrisis and the threat of AI, Descartes was living through a time of great uncertainty and recognized the need for a new paradigm. What he is most famous for is ‘Cartesian dualism,’ the idea that mind and matter are separate. As a Catholic, he didn’t argue that the mind came from matter, simply that the individual mind was separated from matter.

He began a process that would move past merely separating mind and matter, and toward a worldview that saw only matter as real. A contemporary of Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, went further and suggested that thinking arose from small mechanical processes happening in the brain. In doing so, Vervaeke points out, he was laying the ground for artificial intelligence:

…what Hobbes is doing is killing the human soul! And of course that’s going to exacerbate the cultural narcissism, because if we no longer have souls, then finding our uniqueness and our true self, the self that we’re going to be true to, becomes extremely paradoxical and problematic. If you don’t have a soul, what is it to be true to your true self? And what is it that makes you utterly unique and special from the rest of the purposeless, meaningless cosmos?

If the metaphysical foundations of our society tell us we have no soul, how on earth are we going to imbue soul into AI? Four hundred years after Descartes and Hobbs, our scientific methods and cultural stories are still heavily influenced by their ideas.

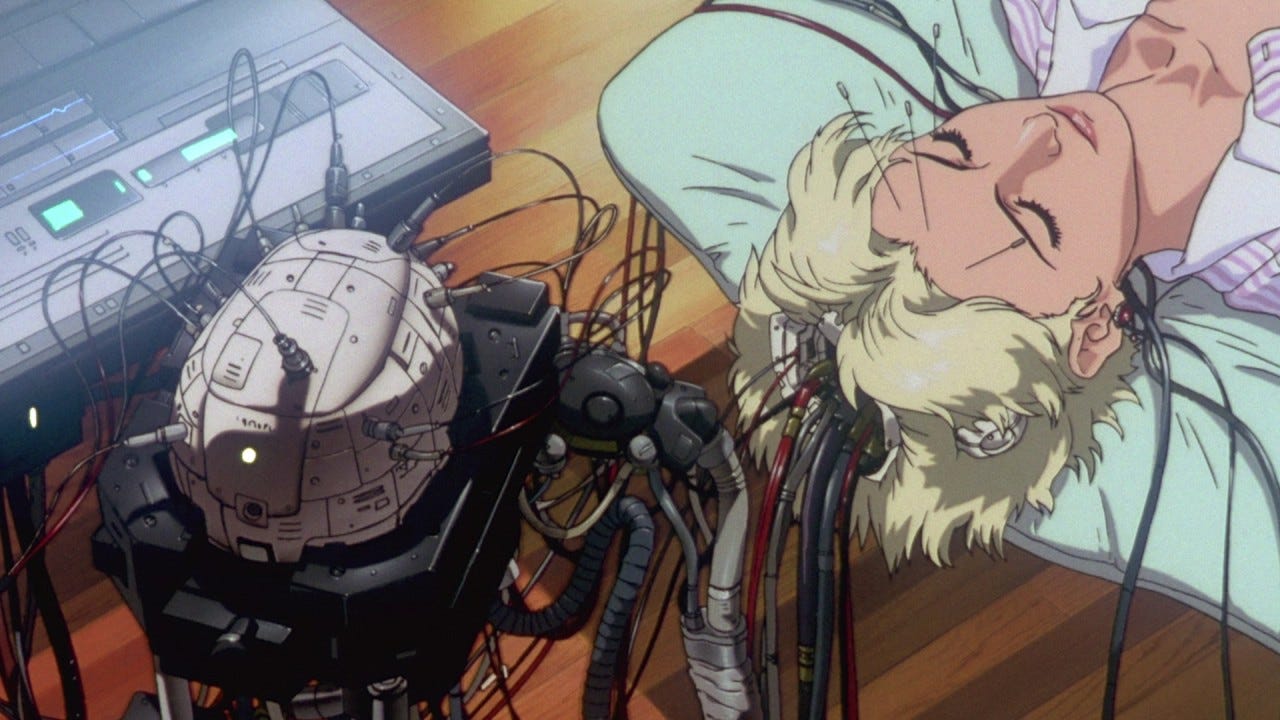

Perhaps the most significant outcome of that is that we still don’t really understand the interaction between matter and mind. The most dominant theory about reality is still that matter is the only thing that’s real - physicalism. Physicalism can tell you what’s happening in the brain when you’re happy, for example, but it can’t tell you what it’s like to be you when you’re happy. It can quantify the code of AI, but it can’t posit what it might feel like to be an AI. Science has no idea what consciousness actually is. This is known as ‘the hard problem of consciousness.’ From a physicalist viewpoint, your experience is a byproduct of matter. Nothing more than an illusion. A ghost in a meat machine.

Physicalism has been successful in many ways, and ushered in vital advancements that most of us wouldn’t want to do away with. However, its implications might lead to the end of all life on earth, so we may do well to start questioning it. Daniel Schmachtenberger has spoken at length about the ‘generator functions’ of existential risk, in essence the deeper driving causes. Two of the most important he points to are ‘rivalrous dynamics [like competitive fish farming]’ and ‘complicated systems [like the economic system of fish farming] consuming their complex substrate [the lake]’. He argues that “We need to learn how to build closed loop systems that don’t create depletion and accumulation, don’t require continued growth, and are in harmony with the complex systems they depend on.”

But what is the generator function of those generator functions? I would argue it’s Physicalism. It has led to a cultural story in which it makes perfect sense to consume until we die, because our lived experience is supposedly an illusion generated by our brains. All the most important aspects of life, what it feels like to love, what it feels like to grieve, are secondary to things that can be quantified. It leaves us with a cold, dead world that isn’t worth saving, and that perhaps, deep down, we want to destroy.

A New View

But what if, instead of the dead machine we have been told it is, the world is actually alive? What if it isn’t just ‘things’ that are real, but the consciousness that perceives those things, as well? The theory that reality is fundamentally a mental process rather than a physical thing is known as ‘philosophical idealism.’

Perhaps the best-known idealist is Bernardo Kastrup. Kastrup holds a PhD in computer engineering and has worked in CERN, also known as the European Organization for Nuclear Research. He also holds a PhD in philosophy, and has been challenging physicalists on what he sees as the fundamental flaws in their view of the world.

When we spoke for my upcoming book The Bigger Picture: How psychedelics can help us make sense of the world, he told me that he’s noticed a significant shift taking place in the last few years in debates on the nature of reality, and he’s found it hard to find anyone who will debate from a staunchly physicalist position. This is partly due to discoveries in quantum physics. But it is mainly, in Kastrup’s view, because the physicalist position doesn’t make any sense.

I have the full conversation with Kastrup available for paid subscribers, as well as an exclusive piece on how DMT experiences can help us make sense of AI.

In a Scientific American article co-written by Kastrup and physicists Henry Stapp and Menas C. Kafatos, they argue that what we’re learning from quantum mechanics points to a reality that is fundamentally mental rather than physical:

Our argument for a mental world does not entail or imply that the world is merely one’s own personal hallucination or act of imagination. Our view is entirely naturalistic: the mind that underlies the world is a transpersonal mind behaving according to natural laws. It comprises but far transcends any individual psyche…. The claim is thus that the dynamics of all inanimate matter in the universe correspond to transpersonal mentation, just as an individual’s brain activity – which is also made of matter – corresponds to personal mentation.

As many Idealists point out, if you think the eyes you’re using to observe nature, your own consciousness, are simply a byproduct of matter, then you come to a philosophical dead end, as that very consciousness is the only thing you can be sure is real. As Andrei Linde, renowned physicist and pioneer of the inflationary universe theory, points out:

Let us remember that our knowledge of the world begins not with matter but with perceptions. I know for sure that my pain exists, my ‘green’ exists, and my ‘sweet’ exists… everything else is a theory. Later we find out that our perceptions obey some laws, which can be most conveniently formulated if we assume that there is some underlying reality beyond our perceptions. This model of the material world obeying laws of physics is so successful that soon we forget about our starting point and say that matter is the only reality, and perceptions are only helpful for its description.

It’s worth noting that idealism isn’t solipsism, the idea that only your experience of the world is real. Similarly, it doesn’t mean ‘nothing is real’. Another philosophical position that seems to line up with our growing understanding about reality is panpsychism. It is similar to idealism in that both positions see consciousness as a fundamental quality of the universe. But there are subtle differences, as philosophy professor and panpsychist Philip Goff explains:

The main difference is that whilst panpsychists think that the physical world is fundamental, idealists think that there is a more fundamental reality underlying the physical world. How can a panpsychist think both that the physical world is fundamental and that consciousness is fundamental? The answer is that we believe that fundamental physical properties are forms of consciousness.

When I spoke to Iain McGilchrist for my book, he shared that he views matter as ‘a phase of consciousness’ in a similar way to how ice is a phase of water – a view that struck me as a useful metaphor for panpsychism. In a panpsychist view, matter and consciousness are one. Every part of the universe contains consciousness.

Quality Metaphysics

So what does a conscious universe have to do with AI and existential risk? It all comes back to whether our primary orientation is around quantity, or around quality. An understanding of reality that recognises consciousness as fundamental views the quality of your experience as equal to, or greater than, what can be quantified.

Orienting toward quality, toward the experience of being alive, can radically change how we build technology, how we approach complex problems, and how we treat one another. It would challenge the Physicalist notion, and the technology birthed by it, that the quantity (of things) is more important than the quality of our experience. As Robert Pirsig, author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, argued, a ‘metaphysics of quality’ would also open the door for ways of knowing made secondary by physicalism - the arts, the humanities, aesthetics and more - to contribute to our collective knowledge in a new way. This includes how we build AI.

It wouldn’t be a panacea. Many animistic cultures around the world have a consciousness-first outlook, and have still trashed their commons when faced with powerful incentives to do so. I don’t argue that a shift in our underlying metaphysics would magically stop us polluting every lake.

However, what it could do is provide us with a philosophical foundation on which we could build new cultural stories. New social games, new concepts around status, new incentive structures. Crucially, it would also change our conception of consciousness as a universal quality of reality rather than a byproduct of matter. In doing so, it opens up new ways to talk about AI being self-aware that could even lead to the birth of a new species of artificial intelligence.

When I asked Bernardo Kastrup what he thought the implications would be of a widespread adoption of an Idealist perspective, he answered:

It changes everything. Our sense of plausibility is culturally enforced, and our internalized true belief about what’s going on is culturally enforced…. They calibrate our sense of meaning, our sense of worth, our sense of self, our sense of empathy. It calibrates everything. Everything. So, culture is calibrating all that, and it leads to problems if that cultural story is a dysfunctional one. If the dysfunctional story is the truth, then, OK, we bite the bullet. The problem is that we now have a dysfunctional story that is obviously not true…. If you are an idealist, you recognize that what is worthwhile to collect in life is not things. It’s insights…. Consumerism is an addictive pattern of behavior that tries to compensate for the lack of meaning enforced by our current cultural narrative…. We engage in patterns of addictive behavior, which are always destructive to the planet and to ourselves, in order to compensate for that culturally induced, dysfunctional notion of what’s going on.

From Game A to Game C

This extends beyond the conversation around AI, and applies to any endeavors focused on mitigating the series of disasters humanity has built for itself. In most cases, organisations and groups focused on tackling existential problems do so from a physicalist perspective. Jim Rutt, one of the founders of the Game B movement, jokingly says that any talk of metaphysics makes him reach for his pistol.

He’s not alone in that sentiment. It feels too abstract, too woo. It’s hard to talk to policy makers about it. But at the same time, one of the recurring questions in different systems-change and activist groups is ‘at what level should we enact change?’ Should we try to change the values of our workplace to be more inclusive, or do we need to descend a level deeper – to the values of society? A well-known phrase in business is ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast.’ Our strategies are derived from the wider culture, and culture is a complex system that can enact change faster than any one individual’s plans.

Our strategies for changing the world are often inspired by a culture created by a physicalist metaphysics. That’s why I propose that metaphysics eats culture for breakfast. What we believe to be real and relevant is the most significant factor in the formation of culture, which in turn influences our thoughts and emotions, which in turn influence our values, which influence our institutions and political policies. The change has to happen at the deepest level if it’s going to have any significant impact on an issue as important as whether or not we go extinct.

Back to the Lake

You own a fish farm. The strange events in your life that led you to owning a fish farm aren’t important right now. What’s important is your quality of life, that of your family, and that of the fish. Your farm is on the edge of a pristine lake, and there are nine other farms dotted around the shore. Sometimes you drink your coffee in the morning, look out over the glistening water and watch your collaborators.

You still have bills to pay, a family to support, and above all, life to live. But there is a safety net waiting for you if you fail, because your culture values the quality of your life over the quantity of what you can produce. You could farm more fish if you turned off your filter, but you are rewarded financially based on the quality of the commons as well as the quantity of fish you farm, so it’s not all that appealing. So you sip your coffee and enjoy the sun glistening on water.

This version of the story is possible. Faced with the existential threats and runaway AI, it might feel unlikely. But if we’re going to have a conversation around building our technology so that it values life, we need to start at the deepest levels of what we believe life to be.

That means exploring not just what we value, but how we value. To remember that our experience of life is qualitative, not quantitative. That everything that matters, from birth to death, is something you feel and experience. If we can draw our technology from those waters, from an orientation toward quality, maybe we have a fighting chance.

A wise and beautiful piece, thank you. McGilchrist’s framing of matter as a phase of consciousness is stunning. In the transcendent/transformational encounter, the experience of the universe’s natural values becomes clear - the good, the true, the beautiful, all qualities far greater than, and preceding, humanity. Nothing we’ve made up, or decided on. Innate to life. Thus the vital importance of the encounter. Looking forward to your timely book!

Excellent piece, Ali!

Fully on board with all the points you make - many of which I include in my own 'forthcoming' book - and it inspires me to be more explicit about the importance of adopting idealism as the accepted cultural metaphysics - as a core part of conceiving how me might transform.

I really like the idea of physicalism being the generator function of the generator functions. It's a wonderfully succinct systems-expression of a very important idea.

Your fish-farm theme is also very nice - except that when you got to the third episode, I was expecting something about a more visceral, personal response (upper left quadrant) - based on an understanding of the interconnectedness of all things and a different motivation by the fish farmer: one inspired by "flourishing" rather than "finance". (I use the phrase "From Finance to Flourishing" to sum up the paradigm change we need if we are to truly change our civilizational system.).

Instead, you provide a systems response (lower left (right?) quadrant) - legislation that takes a more 'flourishing' position by encouraging the protection of the commons. That's equally valid, I guess, but I think it's important to emphasise that we each, as individuals, have to transform, rather than simply expecting and waiting for others to 'change the system' (in ways of which we approve) so that we are incentivised to do the right thing.

But it's still a nice happy ending to the apparently insurmountable multi-polar trap dilemma.

Finally, I have to comment on the video where you chatted with Bernado Kastrup. I've listened to him a lot, and read some books - but that video re-blew my mind! Archetypes, causality, synchronicity, complexity and fractal reality: it took my understanding (and respect) for Analytic Idealism to a whole new level.

All good stuff, Ali!

Alex