The Mythic Rebellion: Why The Far Right Keeps Winning

Immigration, European elections, and Trump's America

The far right is sweeping Europe, eighty years after the Allies stormed the beaches on D-Day. In the recent EU elections, far right candidates won 22% of seats. Emmanuel Macron called a snap election in response, plunging French politics into chaos. In Germany, the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) are the second most popular party in the country.

As in the US, this was an election about immigration. A 68 year old woman living outside Paris told a reporter that she voted for the far-right National Rally because “people feel invaded”. It isn’t just voters of her generation who are rejecting the status quo; the National Rally won 30% of the youth vote, with far-right parties in other countries making similar gains.

I close my eyes. I’m 16, standing at the gates of Buchenwald concentration camp. We walked to the camp on a forest trail, taking the same path many of its victims were forced to march down. The forest was rich with birdsong and dappled sunlight. The camp, surrounded though it was with trees, was strangely silent. A place of so many ghost-cries that even the birds kept their peace.

In Germany, school children visit concentration camps as part of the ’Erinnerungskultur’, the ‘culture of remembrance’. We learn that the slow creep of fascism begins with reasonable-sounding responses to deep grievances. We learn that when it enters the institutions, spreading through the military, the schools, the hospitals, it transforms into a monstrous machine.

If we want to understand why the far right is gaining ground in the Europe, we have to look to the unique role institutions play in the Western psyche. For more than a decade, Western politics has been defined by a rebellion against institutions. Brexit was a rebellion against the EU. Trump was a rebellion against the Washington elite and the status quo; an attempt to ‘drain the swamp’, and reject globalism in favour of America-first nationalism. Covid personalised the rebellion, pitting people against institutional experts and splitting families in the process.

Our politics is no longer a battle between left and right. It is a battle between myths, and our institutions are the battleground. On one side, those who believe that the institutions of liberal democracy can meet the chaos of the times. On the other, people who see those same institutions as the cause of our fragmentation.

The far right is gaining traction because it speaks to a wide-spread frustration with the technocratic bureaucracies of the EU and the US. It casts them as toxic machines enforcing a placeless, multicultural pluralism that serves global capital at the expense of working people. Increasingly, those same institutions don’t have a response good enough to convince voters.

In Europe and the US, we stand at a crossroads in the sun-dappled forest. One path leads to an ethnocentric politics of division and hate, bereft of the beauty of pluralism. The other path leads to more of the status quo: government as a technocratic machine that sees its own populace as vehicles for capital and little else.

Neither path leads somewhere new, but there is another. To find it, we may have to do something that has never been done in Europe or the US, something the political establishment and to the far-right alike would find threatening and alien. The first step is to touch the depths of the Western psyche, and reveal its hidden secrets.

Immigration

I close my eyes. I’m 37, sitting on the London Underground. I’m thinking about this piece, and I look up to see a poem by Benjamin Zephaniah nestled between two ads.

I love dis great polluted place

Where pop stars come to live their dreams

Here ravers come for drum and bass

And politicians plan their schemes,

The music of the world is here

Dis city can play any song

They came to here from everywhere

Tis they that made dis city strong.

(…)

We just keep melting into one

Just like the tribes before us did,

I love dis concrete jungle still

With all its sirens and its speed

The people here united will

Create a kind of London breed.

As the carriage rocks, I savour the beauty of his words. I’m surrounded by people from all over the world, living Zephaniah’s vision of a new culture created by the intermingling of clashing perspectives.

This is the human story in a microcosm, a story of fluidity, reciprocity and strife written in our DNA and our songlines. In his book The Secret of Our Success, Harvard evolutionary biologist Joe Henrich argues that the reason human beings occupy every ecological niche on the planet is because we exchange cultural memes, which in turn alter our biological genes in a process of evolutionary selection. The melding of cultural ideas is what drives both our biological and social evolution.

As Josh Schrei puts it in an episode of The Emerald, the human story is defined as much by travellers as it is by people rooted to place:

“Travellers bring traditions, and those traditions mingle and potencies arise in places that weren’t there before. The power of place isn’t static. To understand place is also to understand the adaptive power of place. Place changes, and people with new understandings of place change place itself.”

If immigration and cultural exchange are such fundamental aspects of human development, why is immigration such a politically charged topic in Europe and the US? Part of the answer lies in why London or Paris are multicultural melting pots, while cities like Tokyo or Shanghai are more culturally homogenous.

It’s because London and Paris are very WEIRD places. This acronym, which stands for ‘Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic’ was coined by Joe Henrich and a team of researchers who began asking whether psychology research, often conducted on Western undergraduates, was truly indicative of human psychology or just people in the West. The latter turned out to be true. In fact WEIRD people are global outliers. As Henrich explains in his book The WEIRDest People in the World:

“WEIRD people are highly individualistic, self-obsessed, control-oriented, nonconformist, and analytical. We focus on ourselves — our attributes, accomplishments, and aspirations — over our relationships and social roles. We aim to be “ourselves” across contexts and see inconsistencies in others as hypocrisy rather than flexibility. Like everyone else, we are inclined to go along with our peers and authority figures; but, we are less willing to conform to others when this conflicts with our own beliefs, observations, and preferences. We see ourselves as unique beings, not as nodes in a social network that stretches out through space and back in time.”

One of the key insights of Henrich’s research is that, perhaps counterintuitively, WEIRD people tend to be more trusting and generous toward strangers than non-WEIRD people, something known as impersonal prosociality. In more collectivist societies, social trust is bound up in kin-networks; complex webs of relatedness and obligation. People outside that network aren’t subject to the same rules or consequences, and so dealing with them is potentially riskier.

Henrich links the evolution of impersonal prosociality to a number of historical factors, perhaps most importantly the Catholic church outlawing cousin marriage.

Along with historical developments like the growth of cities, this drove people to leave where they were born and seek out new opportunities away from home. Henrich explains:

“As life was increasingly defined dealing with nonrelations or strangers, people came to prefer impartial rules and impersonal laws that applied to those in their groups or communities (their cities, guilds, monasteries, etc.) independent of social relationships, tribal identity, or social class.”

While WEIRD people are uncharacteristically focused on themselves and their own success, they are also more generous to strangers, and more willing to engage with those with different views and values. As a result, WEIRD countries like the UK or the US are culturally more accepting of immigrants than many other countries; this is partly why cities like London and Paris are more multicultural than Tokyo or Shanghai.

Impersonal prosociality is made possible because of another WEIRD cultural adaptation. Instead of relying on networks of trust within our in-group, we outsourced our trust to large institutions.

This has profound implications for how we make sense of the rise of the far right, and Western politics in general.

The implication of Henrich’s work is that Western institutions have been the subject of powerful psychological projections for hundreds of years. They act as parent, guardian, arbiter and friend. They offer us home, safety, expansion and opportunity. When I interviewed Henrich a few years ago, we discussed how the loss of institutional trust we’re experiencing in the West is consequently causing inner psychological crises for many of us.

This is why our political yearnings are directed primarily toward changing or destroying our institutions. Defund the police. Drain the swamp. Storm the Capitol. If the institutions change, we think, then maybe our feelings of dislocation and emptiness will change with them.

I close my eyes. I’m 14, walking into volleyball practice. Our coach tells us practice is canceled because a plane just crashed into the World Trade Center. Now I’m 16, sitting under my desk as Mossad agents parole our school’s hallways in a mock terrorist lockdown. I’m 23, being charged by a wall of mounted police at Occupy London. I see the War on Terror. The invasion of Iraq. The bailout of the banks. Corruption. War. Lockdowns. Record temperatures. Record immigration. Record wealth inequality. Someone’s recording George Floyd’s murder. Someone’s recording Trump saying ‘grab ‘em by the pussy.’ Someone’s recording incinerated tents in Gaza.

I open my eyes and see that the promise of multiculturalism, and the beautiful dream it could be, isn’t enough to heal the inner turmoil of our collapsing institutions.

The far right knows this. Researching the policy stances and the cultural messaging of far right groups in Europe, it became clear that the impact of immigration on our institutions is overwhelmingly their largest concern. In the AfD’s manifesto, they state:

“The AfD is committed to German as the predominant culture. This culture is derived from three sources: firstly, the religious traditions of Christianity; secondly, the scientific and humanistic heritage, whose ancient roots were renewed during the period of Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment; and thirdly, Roman law, upon which our constitutional state is founded.

Together, these traditions are the foundation of our free and democratic society, and they determine daily patterns of social interaction in society, and shape the relationship between the sexes as well as the conduct of parents towards their children. The ideology of multiculturalism is blind to history and puts on a par imported cultural trends with the indigenous culture, thereby degrading the value system of the latter. The AfD views this as a serious threat to social peace and the survival of the nation state as a cultural unit. It is the duty of the government and civil society to confidently protect German cultural identity as the predominant culture.”

There is nothing wrong with trying to maintain tradition and cultural identity; we celebrate it when indigenous groups in other parts of the world fight to do this. However, for the AfD the concern is that multiculturalism is a direct threat to the nation state as an institution, and see that institution as belonging to people they consider ethnically German more than anyone else.

The AfD don’t go quite so far as to say this, and like other far right groups have toned down their messaging in recent years to appeal to a wider range of voters. However, the beliefs of its members often differs from the party line. In January 2024, several AfD members attended a meeting where a key talking point was the mass deportation of people with non-German ethnic backgrounds, causing a furore and calls for the party to be banned.

For the AfD, original national identity must be kept culturally pure, and loyalty to the history of the land and its values is a prerequisite for anyone living in the country. For progressives, identity is more likely to be viewed as fluid, and ensuring fairness means allowing displaced or disenfranchised people into richer countries who colonised those countries for hundreds of years.

The problem with both positions is that identity is neither fluid nor pure. It’s both at different times, and in different contexts. Nor is history a clear-cut fairytale about victims and oppressors; it’s a complex flow of relationships.

Going back to a time before multiculturalism is a fantasy. Opening the borders to everyone who wants to come is a fantasy. Instead, something new is being called for in the West. Something radical. But we can’t see what it is until we acknowledge the rift tearing our societies apart.

The Rift

I close my eyes. I’m 9 years old, in the third grade at Frankfurt International School. It’s International Meal Day, and this year I’ve brought Irish soda bread. Some of us are dressed in traditional national outfits, waiting to eat delicacies from dozens of countries from paper plates. It’s a good day.

I went to school with people from over 50 nationalities, dozens of religions, cultural backgrounds and worldviews. We were different in many ways, but the majority shared one thing: socioeconomic class.

We can’t make sense of the political shifts in Europe and the US without looking at class dynamics. In my international school, most of us were middle class or wealthier, and our education was designed to help us thrive in a multicultural, transnational world. Nobody in my graduating class was planning to move to a rural area, get a manual job and start a family. This made us far more similar to one another than to working class people with whom we shared a nationality.

We were, as British journalist David Goodhart has termed it, ‘Anywheres’. In his book The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics, Goodhart argues that Brexit was defined by a rebellion of ‘Somewheres’ against ‘Anywheres’. Somewheres are people whose identity is rooted to place. They tend to be working class, and identify more closely to national or local identity than Anywheres. Over the last fifty years, they have been disproportionately affected by globalist politics of the Anywheres, and used the Brexit vote as a way to fight back.

N.S. Lyons has made a similar distinction between what he calls Virtuals and Physicals. Virtuals are white collar knowledge workers in the cities who predominantly work online. Physicals work with their bodies, growing the food and running the logistics that allow Virtuals to exist, but are unfairly seen as backward, racist and inferior by their city-dwelling counterparts.

Both writers are pointing to a deepening class divide. We can hear the pain of this divide in the music of Oliver Anthony, the country music singer whose song Rich Men North of Richmond went viral in autumn of 2023.

Anthony is one of the people Hilary Clinton was referring to in her infamous ‘basket of deplorables’ speech in 2016:

“You know, to just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump's supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. They're racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic – you name it.… they are irredeemable, but thankfully, they are not America.”

Later in the speech Clinton spoke more empathetically about the "other" 50% of Trump supporters who ‘feel the government has let them down, the economy has let them down’ and are ‘just desperate for change.”

Few people remember that part of her speech. This is probably because her ‘basket of deplorables’ phrase confirmed what many working class people felt: that politicians like Clinton cared more about elite ideology and global finance than the working class, who they regarded with a sneering contempt (if they saw them at all).

Brexit, Trump, and now the far right in Europe have managed to connect with these voters because, as Alex Evans points out in his book The Myth Gap, they told more compelling stories than the establishment.

The right draws on myths about regaining pride and sovereignty; being part of a movement greater than yourself to reclaim your country. The progressive response to the myth gap has been inept for years, and has recently morphed into what writer Alysia Ames has called ‘the omnicause’, a sprawling ideological tent that includes LGBTQ+ rights, environmentalism, pro-Palestinian campaigning and a lot of infighting. As I’ve written about before, its language is designed for elites with college degrees, and is often blind to class due to its obsession with identity politics.

The technocratic elite meet the mythic promises of the far right with the bland, secular humanistic platitudes of a corporate manager. They work in a machine that sees human beings as placeless, rootless economic units who should, like products, spread value across national borders and facilitate the flow of capital. This is why, ultimately, they will keep losing.

The Pre/Trans Fallacy

The myth gap leaves many voters politically homeless. Faced with mythic promises coming from the right, and managerial platitudes from the institutions, it’s tempting to think there are no political choices left, and no way to have a new conversation.

But this isn’t the case. It’s just that the third path is hard to see because the myth gap has left our political conversations stuck in what’s known as a ‘pre/trans fallacy.’

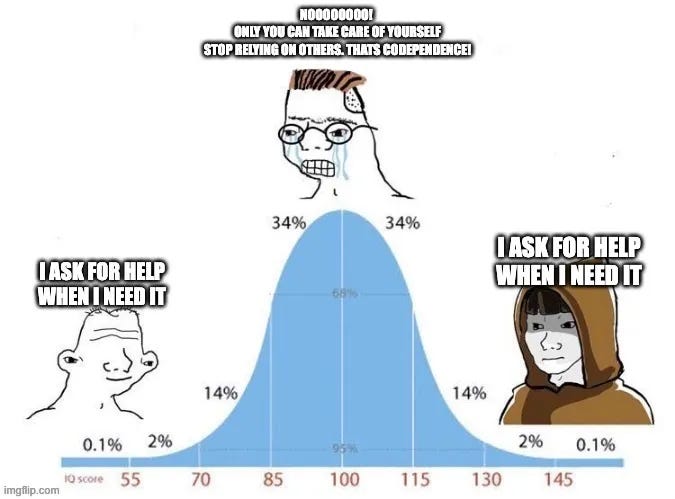

Coined by Ken Wilber, the pre/trans fallacy states that we often confuse the pre-conventional (an earlier state of development) for what’s post-conventional (at a later stage of development) because they’re both unconventional. As Daniel Kazandjian points out, a good example of the way we often confuse dependence, independence, and interdependence in relationships.

Because dependence and interdependence are both ‘not independence’, they are confused as being the same thing.

It is almost impossible to find a trans-conventional perspective on immigration or white identity, because people are terrified of being confused for Nazis. Institutions like the EU are stuck in the conventional perspective, and can only make slight adjustments to a Federalist world-view that sees ‘ever-greater union’ and globalisation as the only realistic choices.

In contrast, the message of the far right’s pre-conventional position is simple and compelling for many who feel let down by conventional politics. It tells them ‘Our land, our language, and our identity is under threat. The woke madness of the technocratic elite is destroying our nation, and we are inviting you to embark on an epic journey to reclaim what is rightfully yours. We give you belonging. We give you meaning. We give you a sense of self-respect and dignity that they’ve taken from you.’

The far right is speaking to deep unconscious desires that, in the absence of a trans-conventional politics, nobody else is speaking to. To find the trans-conventional path forward, we have to transcend and include both of these positions. And that means understanding the strange dynamics of right-wing fantasy.

The Reichsbürger

In an essay I wrote just after the storming of the Capitol on January 6, 2021, I argued that we’re living through ‘The Age of Breach’. The internet is acting as an imaginal realm between our conscious and unconscious minds, and increasingly the place where our political fantasies are swirling into new forms. Sometimes, as with QAnon, these coalesce into a fully-fledged reality that thrives online.

When they reach a critical mass, these psychic energies ‘breach’ the real world, as they did on January 6. Breach events can have a significant impact on the physical world, but they never have the impact the organisers imagined, because the rules of the internet and the rules of physical reality aren’t the same. Guy Reffitt, one of the ringleaders of the January 6 insurrection, told a reporter from his prison cell that when everything shifted from online chats and small in-person conversations to real-life insurrection, ‘Fantasy slammed into reality like a car wreck.’

The latest breach event is perhaps the weirdest yet. In December 2022, 3,000 police officers arrested 25 people across Germany, Italy and Austria in what was Germany’s most largest counter-terrorism operation to date. Their targets? The Reichsbürger, a far-right group plotting to overthrow the government. As reported by Foreign Policy,

“Their ideological views range from the rejection of democracy to elements of monarchism, right-wing extremism, historical revisionism, anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial, and esotericism—a belief that occult, metaphysical, and other similar teachings and practices can lead to self-knowledge and self-realization.”

Their plan was to storm the Bundestag, overthrow the government, seize the military, and return Germany to its pre-1919 legal status. At the centre of this movement was an eccentric aristocrat, Heinrich XIII Prinz Reuss.

Reuss felt personally aggrieved because his family’s old aristocratic seat and property had been part of the former East Germany and his legal battle to reclaim it after reunification had failed. He managed to draw in a group that included an AfD politician, ex Special Forces and military, and a school teacher. The group had a strong esoteric bent, with the AfD politician practicing oomancy (egg divination) and consulting astrological charts to plan the coup (I explore the divinatory aspect of the Reichsbürger and QAnon in the context of AI in this piece). Beyond the core group, an estimated 20,000 Germans consider themselves Reichsbürger, coming together initially through a shared anger about Germany’s Covid policies.

It can be tempting, as many Germans did at first, to see the Reichsbürger as a group of swivel-eyed lunatics. But the Reichsbürger movement points to an important and worrying development in the far-right imaginary.

German academics Christoph Schönberger and Sophie Schönberger are two of the leading scholars on the Reichsbürger movement, and in their book Die Reichsbürger, they place the movement within the wider frame of conspiracy theory groups, defined partly by an attempt to invert the institutional relationship between experts and regular people. However, what’s unique about the Reichsbürger is their obsession with one particular institution: the legal system. As the Schönbergers explain, this creates a unique complexity:

“..in the realm of law, the Reichsbürger cannot be understood as a heterodox alternative scene that gradually pluralizes the field under the wary resistance of official authorities, as is the case in religion or medicine….This is due to the nature of law itself. Orthodoxy in the legal system is both harder and softer than in other societal fields … At the same time, the law is always subject to change through legislation and jurisprudence… However, this change is only possible according to the internal rules of the legal system and through the actors recognized within it…

[The Reichsbürger] do not aim to achieve political goals through the strategic use of the administrative and court systems, but rather imagine their own alternative law, bypassing these institutions, and adorn it with new external symbols of sovereignty.”

Like adherents of QAnon, the Reichsbürger created an imaginal reality for themselves in which the existing institutions weren’t there to be changed on their own terms, but were stripped of legitimacy entirely in lieu of a constructed fantasy. As the Schönbergers explain:

“[They do this by] denying the existence of prevailing law and imagining an alternative legal order, for which the Reichsbürger are now the sole experts. For the Reichsbürger, law as a social instrument is of central importance. They try to transfer the power contained in it to themselves. Through this endeavor, the Reichsbürger make it particularly clear how significant a power resource the law is. Because the law is an instrument not only for discipline but also for the exercise of power: it positions individuals in a power relationship over others.”

The Reichsbürger signal a new phase in the mythic rebellion; delegitimising the law itself. Trump’s trials, and their inability to halt his presidential ambitions, inadvertently serve a similar function: they delegitimise the institution that regulates all the other institutions. That the Reichsbürger weren’t successful doesn’t matter as much as the unconscious insight their ideology points to. They went straight for the institutional jugular. Like the Nazi term ‘Lügenpresse’ (lying press) or ‘fake news’, delegitimising the legal system destabilises consensus reality to open the door for an imaginal reality dictated by the far-right.

In the process, they are seeking to draw out the power trapped within the institutions and repurpose it. It is, for want of a better term, an attempt at magic. And what is magic but the use of imagination to change the world? On the farthest fringes of acceptable culture, movements like QAnon, and the Reichsbürger have tapped into the knowledge that the power within our institutions is held in place not by stone, but by belief. By imagination.

The intentions the Reichsbürger or Trump have for extracting that power are regressive and narcissistic, but that doesn’t mean they’re wrong in their analysis. Our world really is held together by belief and imagination. Used in service of love, creativity and generative growth, this understanding can be profoundly powerful. If other sides of the political spectrum really took this as seriously as the far right, they would open the door for a return of the power of imagination to politics.

But to take that latent creative energy, and to move it from its fearful and egotistic versions toward a more generative expression, we would first have to learn how to grieve.

The Post-Conventional Response

So far, I’ve explored how and why WEIRD psychology places institutional change at the heart of the Western psyche. I’ve looked at why the pre/trans fallacy makes it so hard to talk about alternatives to either the conventional politics or far-right myths, and why the far-right is able to take advantage of this.

It’s time now to step onto the third path. And only a few steps in, I start to feel an overwhelming grief. This is good; this is how it should be.

Psychologist Vamık Volkan, who specialises in large group psychology, sees grief as fundamental to conflict. As Alex Evans explains:

“One of Volkan’s core ideas is that when a group’s identity is threatened after a loss of power, status, or prestige, it becomes psychologically essential to reestablish it. If societies don’t work through their sense of loss through a process of mourning, he continues, it can become central to group identity – which in turn makes them vulnerable to manipulation by destructive leaders who play on old wounds. Serbia and Milosevic offer one example; Trump, with his MAGA story of how America used to be great (and could be again), another.”

Volkan points out that these grievances can be hundreds of years old, based on events that happened well before living memory. They will not shift until they are recognised as grief and processed.

I close my eyes. I am Europe. I am the slow-groan of glaciers. I am dreams daubed on the walls of caves. I am the Reformation and the 100 years war and generations of work and creativity and toil. Blood spattered poppies. Trains to Auschwitz. The hope of unity. I am the multicultural metropolis. I am the grief of the forgotten.

Mourning over what has been lost isn’t just about re-establishing a sense of group identity. It’s also about mourning something beautiful that will never be again.

What if what’s needed in Europe today is a collective process of mourning the loss of cultural homogeneity? Mourning the loss of coherence it brought, and the sense of belonging it gave us.

This is what the pre/trans fallacy makes so difficult. It is taboo to speak of the loss of white indigenous identity in Europe. So taboo, that even to mention it immediately sparks a reaction. In the absence of that conversation, conspiracy theories like ‘The Great Replacement’ fester, and immigrants are seen as invasive and inhuman instead of as equals. In its pre-conventional form, unprocessed grief turns atavistic, racist, and closed-minded.

From a trans-conventional perspective, white European identity can be held within a wider perspective that celebrates multiculturalism and the fluidity of national identity. It is possible to mourn the loss of ethnic homogeneity while at the same time celebrating the beauty of multiculturalism. Not just possible, but essential.

As Josh Schrei has pointed out, we can’t process cultural wounds just by speaking about them; they need to be enacted and processed through embodied ritual. As Roger Walsh and others have argued, this is foundational to shamanic cultures around the world who engage in group dancing, drumming or psychedelic ceremony to process and overcome collective wounds by entering a state of communitas.

Nation states still have the capacity to do this. In the UK, the queen’s funeral and the coronation was a collective symbolic process of death and renewal. When Germany closed its last coal mine in 2018, it did so with a ceremony in which a miner came up from the depths to hand the last piece of coal to the German president, while the head of the mining union said: “For some people this is a stone. For you it should be a symbol of an important part of our history. For us miners, it was our world.”

You can’t celebrate multiculturalism while being afraid to celebrate monoculturalism. They are not mutually exclusive. You can’t tell people to move with the times if you don’t let them first grieve for what they have lost.

As philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues in The Disappearance of Ritual, ritual is an essential part of placing ourselves in the world together:

“We can define rituals as symbolic techniques of making oneself at home in the world. They transform being-in-the-world into a being-at-home. They turn the world into a reliable place. They are to time what a home is to space: they render time habitable. They even make it accessible, like a house. They structure time, furnish it.”

The AfD point out in their manifesto that multiculturalism ignores history. They are right to an extent. But the answer is not to revert to the past, but to add history into the present. To place, through collective ritual, multiculturalism into the wider historical arc of European identity.

In WEIRD countries, it is up to the institutions to provide this ritual cleansing. If they fail in this duty, the populace will find ways to fill the void. And it will be those who hate the institutions most who get there first, and dictate the narrative. The most disagreeable and disenfranchised, the racist and the angry, the power-hungry and corrupt.

Had European governments enacted collective grief rituals after Covid, they may have prevented movements like the Reichsbürger from ever forming. They could have created spaces for people from across the population to voice their anger, and their fear, and their grief. To connect around shared humanity and witness one another. I did this on a small scale for 200 people and the space that opened up was beautiful.

This is possible, because it’s not that we don’t know how to enact ritual; human beings ritualise in the same way ducks swim. It’s that conventional politics has forgotten what ritual is for.

I close my eyes. I see the streets of Berlin and Dublin lined with people of all colours and creeds. I see the elders who knew of a time before multiculturalism standing on stage and telling their stories. I see musicians and artists celebrating their ancestral traditions. I see the young speak of their sense of dislocation, and hope, and fear. I see newer arrivals to the land bearing faithful witness, then bringing their own songs and stories to the stage as equals. I see a collective ritual in which those new to the nation support those whose ancestors were born to it, together processing the grief of what has been lost and the joy of what is to come.

After the Grief

Processing collective grief is only the first stage. Grief opens the door to a new kind of politics, one that allows a full expression of Germaness or Frenchness, while simultaneously celebrating multiculturalism and recognising that those identities are in a continuous process of evolution.

In short, we need to rescue nationalism from the far right by allowing it to sit alongside multiculturalism. When I spoke to Alex Evans for this piece, he pointed out that one of the reasons it can be hard for people to hold a ‘yes and’ perspective with multiculturalism is because we often struggle with the concept of ‘nested identities’; the idea that you can be British and European.

I would go further and suggest that the reason we struggle with it is because those identities are often placed in a hierarchy, with more tribal identities seen as inferior to more world-centric identities by progressives, and vice versa on the right. In fact, they all imply one another, and you can’t nest more inclusive identities on weak foundations. For it to work, tribal and national identity has to be culturally honoured as much as world-centric identity.

That is a job not for politicians, but for artists. All the edginess and taboo-busting danger that the far right are using to engage younger people can be redirected toward a post-conventional perspective that moves beyond bigotry and intolerance, while still challenging conventional politics.

The imaginal dream of a new future is not going to come from the technocratic political class. It absolutely won’t come from the fear-mongering and manipulation of the far right. It will come from a culture that knows how to honour the past while celebrating change. From economic and immigration policies that nurture identity in its many forms while recognising that there is a limit to how much diversity a culture can take. Above all, it will arrive by dreaming of a third path, one that takes us beyond the sterile emptiness of our existing politics into a future defined by love, acceptance and aliveness.

I no longer believe we can talk about left and right and make any sense at all of what's going on. For me now it is the establishment v everyone else. It is The Machine v The People. The left has been subsumed into that which it once at least nominally was against or at least wanted to keep in line. There are many politically homeless people now being defined as "the far right" and though them falling into the Trump camp frustrates me, I can understand, if you don't have a lot of understanding of how the system works, how there is something there that seems different and new. There is certainly valuable info you will get there that you won't in, say, any of the world's dessicated labour parties, whose flaccid ideas about how to fix things always end up supporting the machine. People are legit frustrated that govts are pouring immigrants into overburdened cities because they're not doing the things immigration requires, like building enough infrastructure. Calling those people "far right" is to fall in line with what the establishment says about anyone who questions it. Left and right definitions are not only dead now, but they're damaging to the efforts of everyday people trying to break free from the industrial machine.

A good start to finding a better way forward could be to rise above the polarizing, reductionist, and charged labels of “far right” and “progressive” — and our tendency to use them as convenient baskets for disqualifying by default any views, people or groups we see as unpleasant or disagreeable (typically by associating them with truly horrific acts or disastrous policies cherry-picked to make the case of our choosing). Cognitive distortions and biases abound in this minefield. I have yet to hear anyone define these terms in a way that is constructive, which makes it quite difficult (if not impossible) to frame any solutions atop their shaky ground.

Standing here together at your sun-dappled crossroads, let’s begin to add more nuance and dimensionality to our critical thinking and social debate. Let’s become less “meta” about political labeling, less emotionally influenced by story, and get more real about specific issues, diving beneath the partisan chop at the surface. Let’s start giving more weight to actions than words; let’s focus on solutions to our large-scale coordination challenges, set clear, nonpartisan metrics for proving them out, and continually pivot towards what works — whether or not the findings fit neatly into your or my personal model of the world.

Our future depends upon it.