This piece is written by Alexander Beiner and accompanies a new film we’ve released on the channel

Long before the plague infected our bodies, a sickness was spreading roots in our minds. We’re in the grips of a global mental health crisis, with close to a billion people struggling with some form of mental illness. Someone takes their own life every 40 seconds. A sense of dislocation, anxiety and loneliness pervades modern life.

As psychiatry struggles to find solutions, psychedelics are emerging as beacons of hope. Promising results from a new wave of clinical research suggests that psychedelic-assisted therapy using psilocybin, MDMA and DMT, might not just be more effective than current treatments, but usher in a new paradigm of treating mental health. The last two years in particular have seen a gold rush of investment, with dozens of psychedelic pharma companies raising close to $2 billion in stock market flotations. The press has stopped telling stories about people jumping out of windows high on acid, and instead pumps out glowing headlines about the promise of psychedelic science. Investors like Christian Angermayer claim that psychedelic pharma companies could solve the mental health crisis.

The hype can make it appear as though we understand what’s causing this crisis. We don’t. From the perspective of biomedical psychiatry, our depressions, anxieties and addictions can be fixed with the right drugs. From another perspective, this crisis is a desperate howl from the heart of consumer culture. A howl that warns of socioeconomic disparity, with children from underprivileged backgrounds four times more likely to suffer mental health difficulties than wealthier peers. Of an epidemic of loneliness, and skyrocketing rates of teenage mental illness driven by predatory social media algorithms.

The early promise of the psychedelic counterculture was that these medicines would address the roots of our problems, not their symptoms. That they would decondition us from the cultural values driving us insane by reconnecting us to the sacred. The trajectory of my life has been inspired by this hope. However, as psychedelics have encountered market forces, I’ve felt increasingly cynical. The counterculture vision has been commodified. Not just by biomedical science, but by a narcissistic culture hungry for the latest fix to sell to those stranded on the shores of a dying world.

But over the last year, something has shifted in me. I’ve moved from a kind of premature grief to a renewed hope that psychedelics can play a vital role in helping us find solutions to the crisis of the times, from environmental collapse to political polarisation. This essay recounts the conversations I’ve had over the last year with leaders in psychedelics and other guests we’ve had on Rebel Wisdom. Clinicians, activists and indigenous leaders. Researchers, lawyers and artists. Game theorists, futurists, consultants and occultists. Conversations that have led me to an unexpected hope, and a trickster belief that we can steal psychedelic culture back from the hollow nightmare of a broken system.

Sacred Transformations

The idea that psychedelics can lead to cultural transformation has fallen out of fashion. What’s more in fashion is the latest neuroscience and clinical research. However, the latter provides clues to the former. To find those clues, we can look at how psychedelics work.

Humans have been using psychedelics for thousands of years to widen our perception of reality. Shamanism, including the use of medicinal plants to attain wisdom, is widely regarded to be one of the first forms of human spirituality and healing. In ‘Awakening from the Meaning Crisis’, cognitive scientist John Vervaeke points out that shamanism is often associated with a phenomenon called ‘soul flight’. The shaman might have the experience of transforming into a bird or leaving their body and seeing the world from above. In doing so, they can identify previously hidden patterns. Where the antelope are, a new insight into the social dynamics of the tribe, when it’s going to rain. It’s no coincidence we still talk about ‘getting high’.

Vervaeke sees this as a cognitive process of ‘zooming out’ from our normal frame of reference. He uses the example of taking off a pair of broken glasses. Normally we see through our frames, but when we zoom out we’re looking to our frames. Where are they cracked and smudged? Where are they warping how we perceive? We can then put our glasses back on and ‘zoom in’ through a new set of perceptual frames. This cognitive process, not limited just to psychedelics, doesn’t lead us solely to knowledge, but helps us to cultivate wisdom: the process of learning how to apply this knowledge well.

The neuroscience of psychedelics seems to support this idea of reframing. Robin Carhart-Harris, the world’s foremost psychedelic neuroscientist, has shown that psychedelics lead to neuroplasticity, or our brain’s capacity to change and rewire itself. One reason they may be so effective in treating mental illnesses is that they break us out of fixed, rigid ways of seeing ourselves and the world. Carhart-Harris has suggested that the presentations we see like depression or anxiety could have the common cause of “reinforced, maladaptive habits or biases”. Research suggests that psychedelics work in part by catalysing a window of plasticity in the brain. An opening where we can create new neuronal links, frames, connections and behaviours.

However, it’s not the drug alone that does this — it’s the drug in combination with a practice like therapy. The positive clinical trial data driving the psychedelic renaissance comes from a union between pharmacology and deep therapeutic holding. Psychedelic therapists Maria Papaspyrou and Tim Read recently brought out ‘Psychedelics & Psychotherapy’ exploring this complex and emerging field.

When I spoke with them, they described psychedelic therapy as a process that invites us to confront and move toward our pain, rather than numbing out. It’s a slow, considered, and deeply relational form of healing which presents a different paradigm to traditional psychiatry, in which a doctor intervenes to treat a patient. “The therapeutic process involves a very deep surrender for both the therapist and client,” Maria explained. “Stanislav Grof spoke about the ‘healing intelligence,’ which is the deeper layers of knowing that the participant will open up to. The therapist is not there to influence or guide that, but to move with it.”

Once we’ve had this transformative experience, we need to integrate it. Integration, Maria described, “is about meaning making; making sense of the experience and finding a way to make some kind of use of it in your everyday life.” This brings us back to Vervaeke’s glasses metaphor; integration is like putting your new glasses on.

And at the core of this kind of healing is an encounter with the sacred. This encounter, sometimes called the mystical experience in the literature, is believed by many researchers to lie at the heart of the healing power of psychedelic therapy. Many describe it as a radical reframing: of priorities, of relationships, and of the way we connect to reality.

Me vs. We

If psychedelics can elicit these transformations on the individual level, can they do the same on the cultural level? To many of us, the cultural landscape of 2021 feels like a collective version of the “reinforced, maladaptive habits and biases” pointed to by Carhart-Harris. We’re stuck in rigid ideologies. We seem unable to zoom out and have generative conversations. We can’t agree on what’s true anymore, whether that’s vaccines or gender or history. This breakdown in collective sensemaking is an existential threat; it renders us unable to reframe our social values or develop policies fit for the complexity of the times. We’re stuck in old stories, old certainties and endless grievances.

John Vervaeke often draws on the work of neuroscientist Marc Lewis, who has argued, in a similar vein to Carhart Harris, that addiction and depression might be a process of ‘reciprocal narrowing’. Our cognitive framing gets stuck in a feedback loop, and our ability to think outside of our frames becomes narrower and narrower until we can’t free ourselves. Psychedelic experiences may be an example of an opposite phenomenon: reciprocal opening. Our frames expand more and more, giving us new perspectives, increasing our cognitive flexibility, and connecting us to the rest of nature.

But giving everyone LSD and hoping the world will change doesn’t work. Psychedelics famously rely on set (your mindset) setting (your environment) and dose (how much you take). Equally important is context, the wider cultural framework you’re taking them in, and the expectations, assumptions and theories of reality you bring to the experience. Researcher Betty Eisner referred to this as our ‘matrix’.

Ken Wilber has argued that we always interpret a state (like dreaming or tripping) through the lens of our stage of development and our cultural conditioning. An inuit in the 1880s didn’t have the same kind of trip as a stock broker in 2021. As Erik Davis has pointed out, the cultural narrative around psychedelics changes the experiences we have. As we widen our frame, we must have a cultural container for it to widen into. In most cultures that have used psychedelics, from the modern Shipibo to the ancient Greek, the experience has been embedded in a complex cultural narrative that helps people make sense of their experience.

But what if your culture can’t help you contextualise your experience, because it doesn’t have space for the sacred and transcendent? Here lies the problem of psychedelic capitalism.

The Psychedelic Trojan Horse

To unpack this problem, we need to look at how psychedelics are entering the mainstream. To pull this off, the psychedelic pioneers of the last 50 years used a tactic that I call ‘The Psychedelic Trojan Horse’. They realised that the quickest, and perhaps only, way to get psychedelics out of the underground would be by hiding them in a container of medical science. The people pushing the horse — psychedelic scientists, researchers, activists — made a tacit agreement to be less challenging to the status quo. Less weird. They’d put on suits and speak the language of the clinic and the boardroom.

In many ways, this tactic has been tremendously successful. Research is booming in psychedelic science. Celebrities like Will Smith now talk about their ayahuasca journeys. Psychedelic pioneer David Nutt, who leads the famous Imperial College Psychedelic Research Group, pointed out when we spoke that most of the resistance to legalisation is now coming from more conservative clinicians within the medical establishment; a recent study he conducted suggested that almost 60% of the general public are in favor of reclassifying psilocybin. But despite its undeniable success, the Psychedelic Trojan Horse has had unintended consequences.

When it comes to psychedelics, the horse is more important than what’s inside it. If you give away the horse — the dominant cultural narrative around psychedelics — you give away control over the experience itself. Big pharma, the wellbeing industry and biomedical psychiatry start to create narratives around what psychedelics are, who they are for, and how they should be used. Inevitably, the following results. JR Rahn, former chief executive of MindMed, put it strikingly in a Forbes interview: “I want nothing to do with those kinds of folks who want to decriminalize psychedelics… you don’t have to be a revolutionary [to bring these drugs to market]”.

The God of Zero Sum Games

And it’s precisely the fact that you don’t have to be revolutionary to bring psychedelics to market that’s the issue. To see why, we have to involve an ancient Canaanite god called Moloch. Moloch was a deity to which the Canaanites sacrificed their children — an unrelenting, hungry god of war. He was revived by Allen Ginsberg in his poem Howl, which casts Moloch as an ever-present and unseen force driving the world toward disconnection.

Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgment! Moloch the vast stone of war! Moloch the stunned governments! / Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money!

Later, Moloch was popularised by essayist Scott Alexander, who for the first time linked the metaphor to game theory: the branch of mathematics that analyses competitive dynamics. For Alexander, Moloch is the perfect metaphor for the incentive structures within our economy that inexorably lead to winner-takes-all outcomes, regardless of the intentions of individual actors. As former poker pro and YouTuber Liv Boeree told me in a recent film we put out,

“If there’s a force that’s driving us toward greater complexity, there seems to be an opposing force, a force of destruction that uses competition for ill. The way I see it, Moloch is the god of unhealthy competition, of negative sum games.”

A key concept for understanding Moloch is the concept of the ‘multi-polar trap’. This is the idea that, when individual actors are given the incentive to do something which is detrimental to the group as a whole, eventually everything goes to shit for everyone. As Boeree pointed out, as soon as one social media company started using hidden beauty filters, all the others had no choice but to do the same or lose engagement. In the process, they made the overall social media environment worse for everyone’s self esteem.

It is exactly this inadvertent race to the bottom that is explored in ‘We Will Call it Pala, a wonderful short story about psychedelic mainstreaming written by Dave McGaughey. It tells the story of a young woman whose life is changed by psychedelics. She ends up creating a clinic, but slowly her dream is transformed into a consumerist nightmare as she has to compete with other clinics at the cost of patient care. Its sequel, In the Light of Dying Stars, expands on the theme.

As Jamie Wheal pointed out when we spoke, many researchers and academics in the legacy psychedelic community seemed naive to these game theory dynamics when they first started engaging with venture capitalists and pharma execs. Many of these for-profit players came into the ring telling touching stories about their own psychedelic experiences.

‘[the narrative of] I’ve looked into their eyes, I’ve seen their soul, we’ve broken bread, we’ve tripped for a night and they’ve told me their “profound journey” story which brought them to this “space”?” Jamie explained. “All those things go out the fucking window when we have the multi-polar trap.”

The sacred means nothing to Moloch. Just as oil companies ‘green wash’ themselves to appear environmentally conscious, psychedelic companies are incentivised to ‘tie dye’ their image as caring and conscious. Whether it comes from an authentic desire or not is largely irrelevant.

Moloch’s Patents

The best example of these game theory dynamics showing up in psychedelics is in the battle over patenting that hit headlines in early 2020 and is still raging. Many felt that these companies were filing over-broad patents with the intent of cornering the market. For those interested, Shayla Love at Vice and Anne Harrison at Lucid News have covered this in detail in several excellent articles, while psychedelic patent lawyer Graham Pechenick regularly posts about it on Twitter.

In May 2020, I had a public debate with Lars Wilde, co-founder of the largest psychedelic pharma company, COMPASSPathways. In it, I argued that the aggressive patent strategy COMPASS and other psychedelic pharma companies are taking is not only unethical, but will kill innovation in the field by shutting down the competition. Wilde’s counter-argument was that Compass was pursuing a strategy of patenting because it’s the only way to ensure essential medicines get to people who desperately need them. He maintained that COMPASS wouldn’t try to shut down the competition or prevent people from growing mushrooms for personal use, but my argument was and remains that Moloch gives them no choice but to.

Rick Doblin, who heads up the not-for-profit MAPS (The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies), told me that patenting is not the only viable incentive for working with drugs like psilocybin that are off patent. Another is data exclusivity, which gives you rights to your own data for up to 10 years. MAPS has been using a not-for-profit model for the last 35 years to make MDMA a legal medicine — they are on the cusp of doing so. However, Doblin pointed out that it’s become harder and harder to raise money philanthropically. As an investor, you could give MAPS £1 million with no return, or give a pharma company £1 million and perhaps get £1.2 million back. Moloch cracks his knuckles.

But this works both ways, and being free of investor influence allows MAPS to behave differently. “One way we’re different from for profit is that I spend a lot of my time going to where the trauma is, not where the money is,” Doblin told me. “We’ve just done some projects with Centre for Victims of Torture in Ramallah in the West Bank… We’re also trying to work in South Africa and Rwanda and Somaliland, where there is enormous amounts of trauma. But these are not money making situations. The concern is that if you take funds from investors, your focus gets narrowed to ‘where do I give returns to the investors’ or ‘where do I pay back loans?’”

To many, these not-for-profit alternatives to psychedelic mainstreaming feel closer to the original countercultural vision, and also less liable to capture by a broken system. Not-for-profit pharma companies aren’t the only alternative. There are others that may be even more promising.

The Holy Mountain

In 2015, a married couple climbed Mount Rainier in Washington and took magic mushrooms. Tom and Sheri Eckert were contemplating a monumental task. Both therapists, they had been inspired to launch a political campaign to try and legalise psilocybin therapy in their home state of Oregon. Tom described to me what happened next.

“There was a period of silence between the two of us. I was in my own head thinking about the implications of taking this on. And my mind went into the future, thinking about what historians would think about our time, and our way of living. I concluded that they probably wouldn’t care so much about our technologies or stupid politics. I think they’d really notice how disconnected we are from our inner resources, the healing forces within us… and I began to see that this was an important piece to that evolution. Psychedelics aren’t a panacea, but they are a step in the direction of getting reconnected.”

His thoughts were interrupted by Sheri, who turned to him and said ‘I think I’m pregnant.’ Knowing they couldn’t have children, Tom was pulled from his thoughts. “I think this is our baby”, Sheri explained. “And we can raise it just like a child.”

Reflecting in 2021, Tom became pensive. “That was so meaningful to me. It immediately settled me and I thought ‘OK, we’re doing this.’”

Sadly, Sheri passed away in December, 2020. But not before she and Tom had successfully legalised supported adult use of psilocybin in Oregon. The success of their Measure 109 means that psilocybin therapy won’t rely on venture capital-funded, synthesised psilocybin. Mushrooms can be grown naturally, administered by therapists and ultimately stand as the responsibility of the Oregon state health service.

Measure 109 is currently in a two year grace period to figure out exactly how this will work. Tom explained that it’s likely they will adopt a two-tiered model, with qualified therapists treating people suffering from clinical issues like depression or anxiety, and non-credentialed practitioners working with people who want to focus on personal growth or less serious conditions.

Indigenous Reciprocity

Measure 109 was inspired by a belief that psychedelics connect us to a deeper value system. And it is this belief that is inspiring other conversations in the space, such as the one around indigenous reciprocity. This is a concept that psychedelic pioneer Dennis McKenna felt especially concerned with when we spoke, having spent decades working with indigenous groups as a psychedelic ethnobotanist.

“I’m not anti-capitalist”, he explained. “But I am pro-ethics. Here’s the issue; if psychedelics are going to be integrated into mainstream society, we have to recognise their origins are in indigenous societies. And we owe big debt to them for being the stewards of this knowledge for essentially thousands of years…We need to acknowledge that debt.

A number of organisations have started to focus on indigenous reciprocity. I looked at two in particular: a charity called The Chacruna Institute and a for-profit called Woven Science. Chacruna is headed up by Dr. Bia Labate. An anthropologist by training, she echoed McKenna’s sentiment.

“It was by studying the indigenous people’s rituals, shamanism, practices and ceremonies that scientists learnt a lot about the therapeutic potentials of psychedelics. There is a continuity between shamanism, underground ritual, traditional practices and then underground therapeutic circles through to the above ground clinical trial FDA approach … One famous example is how researchers in Canada participated in Native American teepees, and by observing how Native Americans use peyote to treat alcoholism, then proposed a similar study with LSD.”

Chacruna’s initiative sees them acting as a connector and supporter of various indigenous organisations they spent over a year finding and building relationships with. Woven Science recently published a report on indigenous reciprocity, and take a more market-based approach. This includes partnering with indigenous businesses like Kené Rao, an IP defense fund and mini-factory run by Shipibo-Conibo people in the Peruvian Amazon.

Kené Rao is led by Demer Vasquez, one of only three Shipibo-Conibo lawyers. He told me that, from his perspective, medicines like Ayahuasca — which are sacred to the Shipibo-Conibo — can’t be seen as distinct from the cosmological framework around them. Kené Rao wants to protect the traditional art, the Kené, as the intellectual property of the Shipibo-Conibo, along with having a say in how ayahuasca enters the market. This may include a right over some of the profits that come from this cultural IP, which would be funnelled back into the community. In some ways, it’s the Shipibo-Conibo equivalent of the Champagne region of France owning the rights to their unique brand of wine.

While a charity, Kené Rao is trying to play the game of market capitalism to become self-sustaining through sales and licensing. Chacruna is taking a different approach. But both rely on the wider incentive structures of our economic system; Chacruna needs donations from organisations within it, while Kené Rao needs to compete within it. Neither are truly free from Moloch.

Defeating Moloch

A key question for me over the last year has been whether these alternative approaches will be able to create a psychedelic ecosystem that can’t be dominated by the for-profits. Many people I’ve spoken to have suggested that what we’ll likely see, as psychedelics go mainstream, is something like what we’ve seen with mindfulness and yoga. While the dominant cultural narrative around these sacred practices has reduced them to stress reduction and Instagram narcissism, a deeper expression always survives. There’s a Vipassana for every Headspace. Somehow, the sacred shines through.

But the more I’ve been involved in the conversation around psychedelic mainstreaming, the more I’ve come to believe that this is not enough. Personally, I am not content with the small glimmer of something greater. We have an opportunity to see whether the true transformative potential of psychedelics can change our broken game, and teach us how to play a new one.

And as I considered this, I kept coming up against a paradox. It haunted me for months, and goes something like this: psychedelics can change our minds, but only if we’ve already changed our minds. They can transform culture, but only if culture has already been transformed.

It eventually led me to focus hard on the horse, rather than what’s inside it. Instead of trying to mainstream psychedelics into our existing cultural narrative, I believe the focus should be on mainstreaming them with a new cultural narrative. The real issue isn’t psychedelic capitalism, but the culture that selects for it.

In the grips of a meaning crisis, consumer culture is adrift, purposeless, disconnected. The role religion used to play has been filled by alternatives that aren’t designed to fill its shoes. Wellness culture asks us to be well but doesn’t explain what we’re being well for. Tech utopianism bypasses the pain of existence by fantasising about transcendence. We can’t mix and match indigenous frameworks unless we come to terms with the indigenous narcissism of Western psychology. New Age thinking is a mess of self-deception and wish fulfillment. The religion of psychotherapy might bring us some peace, but it doesn’t give us an ontology. Scientific reductionism can measure our pain, but can’t help us to feel it and live with it.

But how do you build a new culture — and is it even possible for the diverse groups who use psychedelics to come together and do that? These questions got me interested in how culture actually changes, and to find out I spoke with Harvard psychologist Joseph Henrich. Henrich has argued that human cultural evolution and innovation emerges through a process of recombination. As different groups share ideas, technologies and other artifacts, we create new combinations; new ways of seeing, being and doing. Some never make it, but others are selected for evolutionarily and end up becoming new innovations, new languages, new religions.

Another aspect of Henrich’s work which I found crucial is his research into WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic) societies. One thing his research has shown is that the game theory outcomes of WEIRD societies are not necessarily those of non-WEIRD societies. Why? Because the cultural values that dictate their choices are different. Moloch is not universal.

New Cultural Frames

If culture emerges through a process of different groups combining ideas and practices, what if we were to do it intentionally? What if the various groups for whom psychedelics are sacred or meaningful were to actively engage in a process of cultural recombination, with the intention of creating a new psychedelic meta-narrative that can counter Moloch? A narrative diverse and universal enough to hold multiple perspectives, from indigenous and clinical to ceremonial and countercultural.

This idea of creating culture rather than passively receiving it lies at the heart of the psychedelic counterculture, and was one of Terence McKenna’s most important contributions. Psychedelics give us the creativity, the connectedness and the insight to step into our own agency, both individually and collectively, and imagine something truly new.

And precisely because culture is fluid, dynamic, changing and evolving, we can have a significant impact on changing it if that’s where we focus our attention. Terence McKenna once said ‘I’m a meme spreader’. I believe what’s needed now is memes that are more compelling than Moloch. Memes that contain within them a connection to something more important than winning at any cost, or blind consumption, or identity status games.

Sociologists differ on what constitutes culture, but a simple version is values, beliefs, symbols, language, artifacts. With this in mind, I believe a good starting point in this conversation is to identify what it is that the diverse psychedelic tribes actually believe and value, and if there are any shared values to start from. To find out, I’m launching a piece of research in 2022 called the Psychedelic Values Survey to identify and map the many diverse people and groups for whom psychedelics are meaningful and important. The data will be used to create a report, then open-sourced to anyone who wants to use it for non-profit purposes. My hope is that it starts conversations around creating a new cultural narrative around psychedelics.

The Sacred

Perhaps this new cultural narrative will emerge naturally as psychedelics continue to go mainstream. I think what is more likely is that we’ll have to consciously build it. And for this meta-narrative to be strong enough to defeat Moloch, I believe it has to be grounded in the one thing that can reliably overcome bad incentives.

The sacred. Something beyond our own egoic needs. Something mysterious and transcendent that reframes the very experience of being human. This is a message we hear again and again in spiritual traditions around the world. It’s the Gnostic connection to true inner wisdom that helps escape the evils we create through self-delusion. It’s escaping Samsara. It’s the red pill Neo takes to escape the Matrix.

The sacred doesn’t have to be spiritual. In sociology, it’s been framed as whatever we set apart as of a higher value than our own self-interest. Durkheim argued that society is always in a dynamic between the sacred and profane. That even though modernism has stripped away religion from daily life, we cannot help but make things sacred. Jeffrey Alexander has built on this tradition, arguing that the cultural construction of the sacred and profane is an essential part of social life, moving ‘far beyond the realm of traditional, institutional religion to shape political life and civil society more generally.’

I believe a defining feature of the age we’re living in is that we make the sacred profane, and the profane sacred. Careening between nihilism and narcissism, we have no idea how to treat something that transcends our egos when we find it. We make it a lifestyle choice. We put it on Instagram. We cut it into manageable chunks to microdose our way to success in whatever fluorescent dystopia we’re building. We play a game of humble-bragging one-upmanship to show how spiritual we are, while secretly caring only about what spirituality can give us. How it can make us a better mother. A better person. Help us unlock the secrets of Bitcoin.

In our desperate, addicted quest for our own salvation, we have forgotten an ancient truth about the sacred. It is recounted beautifully by the classical scholar Peter Kingsley in ‘Catafalque’, his biography of Carl Jung.

“Right at the core of Jung’s life and experience lies an awareness that one comes face to face with the reality of the sacred not through sanity, but in the terrifying depths of madness. And there — in the confrontation with madness — is where our normal, collective sanity is seen for the even more horrifying insanity that it really is. Then, every fixed idea one ever had about anything comes permanently crashing down; and the search begins to find some language that can say what everybody thirsts for but almost nobody wants to hear.”

The sacred is not there to make our lives better. It is not there to confirm our warped ideologies. It is there to shred us. It guides us to the depths of ourselves to find our own delusions and dispel them. Psychedelics were originally called ‘psychotomimetics’, because they were thought to temporarily induce insanity. It may be that going temporarily mad is the only way to see how mad we already are.

My own personal experience with psychedelics is defined by this sacred shredding. I have come to them, broken and lost. Immature, arrogant and blind. They have held me, taught me, shared their wisdom and asked for nothing in return. But I hold them sacred not just because of the unconditional love they have shared, but because they have radically shaken me, forced me to question my deepest preconceptions and my most fundamental connection to reality.

This aspect of the sacred — its capacity to reveal the deep pathology of the cultural games we play — is the burning heart of the psychedelic counterculture. Without honouring it, psychedelics won’t transform culture. They won’t help us to address the problems we’ve created for ourselves, whether mental illness or ecological collapse.

They can only do that if we allow them to reveal our own cultural madness until it’s so undeniable we have no choice but to transform.

You can watch the film version of this essay here. We’re hosting a live dialogue and Q&A with Jamie Wheal and Liana Gillooly of MAPS and The North Star Pledge on 13 January, 2022 — find out more here.

For some reason the current discourse around psychedelics feels a lot like the discourse around the web (in its early days) as well as the discourse around mindfulness. In both cases, the subjects have been co-opted by consumerism, but not entirely consumed by it.

The web was supposed to bring a kind of utopia, and it feels like only the faintest vestiges of that vision still remain. But those corners of the web are wonderful, and powerful in their own ways. As for mindfulness, corporations have latched onto a self-serving notion of it, a way to wring more out of people. They have framed mindfulness practice as an intervention to help employees cope, but cope with what? With the problems of modern life that corporations subject us to in the first place. But this co-opting hasn't destroyed what's actually valuable about a true mindfulness practice.

Modern corporate/consumer culture has perverted much the web, and embraced a perversion of mindfulness practice, and I can easily imagine the same thing happening with psychedelics. I think it's inevitable that psychedelics will be co-opted and perverted by modern corporate/consumer culture. But this perversion will exist simultaneously with truer and deeper engagement with psychedelics.

It will be important to have people like you around to help the rest of us navigate between these and stick to the healthy paths.

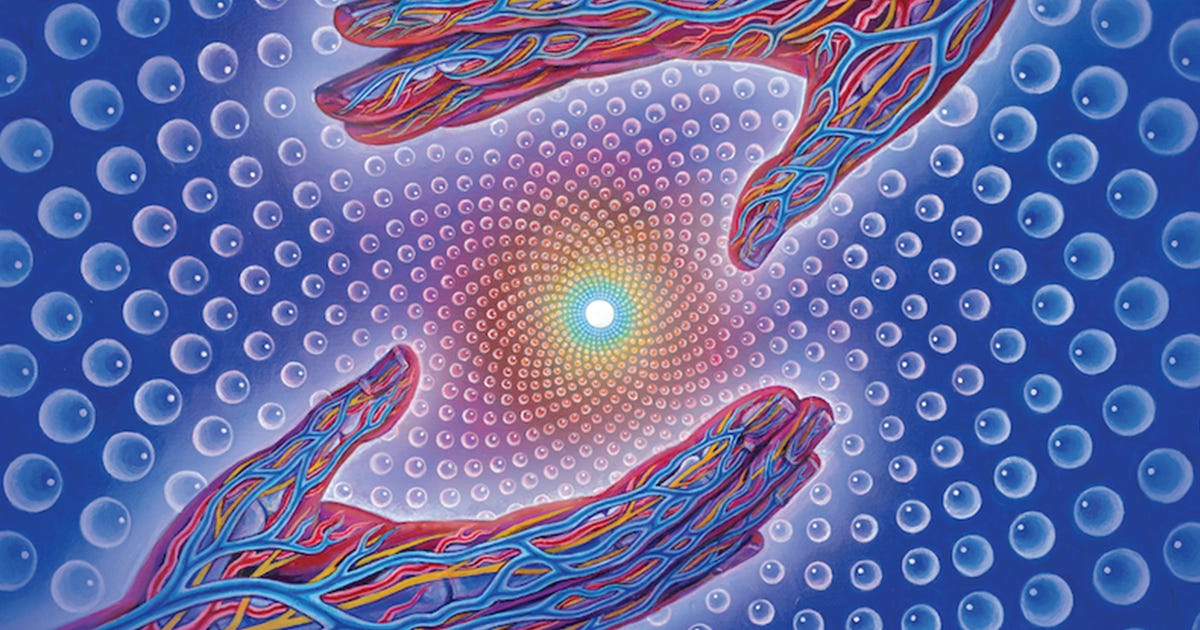

Thank you for this great piece. Balanced and nuanced as always with RW. It was strange to see the painting by Mark Henson, hell future to the left, paradise lost to the right, an almost exact "copy" of a painting I saw when I was crossing the border between Zambia and Malawi, 2003. Probably a copy of Hensons work.