Turn On, Tune In, Drop In: Psychedelic Conflict Resolution and The Origins of Life

Announcing a free online summit featuring 40+ Psychedelic Experts

Changing your mind isn’t the same as changing your clothes. You are a living, breathing experience and you reshape, adapt, and expand every time you alter your perception. It’s not a solid object called ‘the mind’ that changes, but a web of connections. When we think in new ways, what we’re transforming is how we relate. To ourselves, to one another, and the cosmos.

This is why psychedelics hold such potential for helping us navigate the crisis of the times. Not just because they can inspire new ideas, but because they can change the underlying processes that influence the way we think. This is a core argument of my book The Bigger Picture, and understanding how psychedelic experiences can lead to individual and social change has been an obsession for most of my life.

Over the last six months, I’ve been interviewing the leading voices in the field with this question, and many others, on my mind. I’ve spoken to neuroscientists, artists, and clinicians. Anthropologists, indigenous practitioners, NASA scientists and historians. It’s all been part of a collaboration with Conscious Life, who asked me to co-host their Psychedelics Super Conference, a free online summit that launches on May 20 and runs for a week. Along with my co-host Meagen Gibson, we’ve had over 40 conversations with some of the most interesting voices in the field, including Robin Carhart-Harris, Paul Stamets, Laura Dawn, Rachel Yehuda and Erik Davis.

I’m no stranger to psychedelic research, so when I started this project I was fairly sure I wouldn’t learn that much in the process. But in a strange parallel to my trips, I kept getting slapped on the head with a multi-coloured humility stick. I had conversations that left my jaw agape, my heart racing and my mind whirring. In this piece, I’m going to share a few of my favourite moments, particularly the ones that led me to new insights around the topics I’ve been writing about recently.

I’ll recount how a psychedelic journey led a scientist to a major breakthrough about the origins of life. How an Israeli researcher and Palestinian peace activist brought Israelis and Palestinians together for ayahuasca ceremonies for conflict resolution. What a Zapotec psychologist learned about reality through Indigenous weaving, drumming and dancing, and what these diverse experiences can reveal about new ways of knowing we can access right now.

The Origins of Life

I opened this piece by suggesting that the power of the psychedelic experience lies in its ability to change the underlying grammar of our perception. As cognitive scientists like John Vervaeke have argued, this is potentially significant because we can ‘exapt’ ways of seeing and being from one state and apply it to another. In fact, this is likely how our cognition works on a fundamental level.

The implication is that what we learn playing sports, meditating, taking psychedelics or walking across hot coals, can be applied directly to other domains in our lives, like starting a business, healing a relationship, or navigating the meta-crisis.

There are fascinating examples of this in the history of science. Nobel prize winner Kary Mullis, who discovered the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) credited his discovery to insights he had on LSD. “Would I have invented PCR if I hadn’t taken LSD?” he asked. “I seriously doubt it […] I could sit on a DNA molecule and watch the polymers go by. I learnt that partly on psychedelic drugs.” Rumours abound that Francis Crick, who discovered the DNA double helix, was also influenced by his psychedelic journeys. Steve Jobs certainly was, describing LSD as “a profound experience, one of the most important things in my life.”

The latest example in this colourful history of psychedelic revelation is complexity scientist Bruce Damer, who is part of a team at UC Santa Cruz studying the origins of life. I met Bruce last year and have since become involved in his MINDS project, a newly founded psychedelic incubator designed to help people come up with impactful new ideas to tackle humanity’s greatest challenges.

My first meeting with Bruce was memorable, not least because at one point during our meal he pulled out a small vial and asked me to give it a sniff. As I did, I noticed a tiny piece of rock at the bottom of it. It smelled vaguely smoky. He told me that I’d just smelled the oldest thing on earth, a fragment of the Murchison meteorite which has been around for 7 billion years, and may contain the building blocks for life. What I didn’t know at the time is the psychedelic-assisted scientific discovery he made that led him to found MINDS. Below is an excerpt from our interview for the conference, where he describes that extraordinary story.

Alexander Beiner: How did you start studying the origins of life?

Bruce Damer: Dave Deamer and myself at UC Santa Cruz started working together 15 years ago. He had a fantastic chemistry background, 50 years in chemistry; he's the inventor of the nanopore sequencing technology that you hear about all over the world. I had a computational and complexity thinking background, and we put together a model of how life could begin on the earth.

Instead of it being in the oceans, [we theorised] that it started back in Darwin's warm little ponds. Darwin thought 150 years ago that life started in a warm little pond with protein compounds (polymers) forming, and getting ever more complex. Dave had discovered that if you wet and dry little ponds in little dishes, or you sit next to a hot spring and you literally let the exposed mineral surface dry down, you can form little blobs called proto-cells that contain polymers that self-assemble while drying.

That little pool is full of these glowing spheres, if you will, that are protocells. They're the first step toward living cells. He demonstrated this in the lab, and we went out to hot springs around the world, to the flanks of roaring volcanoes or steaming pools, and actually demonstrated it in the wild.

Alexander Beiner: How was that related to the insights you got on psychedelics? What problem did your experience help you crack?

Bruce Damer: Between 2009 and 2013, Dave had trained me. I had this wooly brain, mostly from software and virtual worlds work. I'd been doing work for NASA: spacecraft design, whole mission designs, and the first reference design to take humans to the surface of an asteroid. I did about 25 projects for NASA.

So, I was already doing very creative work, but I really wanted to work on the origin of life. I had wanted to work on this problem since I was about 14 years old. Everything I had done in the previous 30 years had been to build up my knowledge base, but I didn't have the specific training. So Dave gave me stacks of papers, introduced me to all the people in the field, including Nobel Prize winners.

I got the training through osmosis, through reading all this new science I'd never looked at: membrane biophysics, polymerization, combinatorial selection, and then the hot springs themselves. Their potency, their pH and their cycling times and the rocks that they're sitting inside, all those sorts of things. I learned that very deeply. We reached this sort of stopping point where we could see how we could form the protocells - they would bud off and float into the pools - but we couldn't see any further than that.

So I set that problem up in my mind for three years, and on an excursion to Peru with my regular group of ayahuasca drinkers in the fall of 2013, two things happened. The first thing that happened was a breakthrough in my own healing. I was given the experience of my own conception and birth. The feeling of being in my mother's womb and feeling the love just as they decide to give me up (because I was adopted straight out at birth).

Adoptees have this kind of rupture that happens. They're put into an adoption ward with 50 other babies, and they just don't get the attention. They never see or smell the mother. And they have a higher proportion of various psychological traits.

So, I literally saw them giving me up, in love, for my benefit. I felt my mother's love for the last time as a developing baby at post-embryo. And that's the feeling I needed to ground myself to heal the hard knot of pain that was in my belly. And it dissolved. That hard knot of pain was me, the unborn me. So it was a profound experience.

I came out of that and I sort of turned to Mother Aya, and I thanked her for her good works. Then I said, “How would you like to go back to the birth of us all?”

And so we merged and we plowed through, going backwards through the sperm emerging from my father's body, and emerging from his father's body. If you just trace that, you can trace yourself all the way back through the animals and the fishes and then the worms and then the multicellular blobs. Then all the way through the microbial cloud of join points. [I had] this visualization of traveling back in time four billion years, and ended up floating and coming out of the cloud over a Hadean Island, 4 .1 billion years ago, then diving into the warm little pool, seeing the protocells.

Then I became the proto-cell itself. I woke up screaming because my body was now this gelatinous mass, this combination of polymers struggling to do the lifelike thing, and I noticed that a part of me was tearing off and creating this black vacuole. I realized it was a failed division, and that death had to happen to write the code of life.

I could watch sort of an undulating piano key action in polymers within myself. So that was the incredible peak of the experience, and it was the clue that led to the insight that gave us the complete cycle of proto-cells and polymers coupling between the wet phase and the dry, going back into the layers and wiggling around and competing.

I got the entire download about two months later after the questions posed by the ayahuasca experience. It came in a breathwork session, an endo trip [endogenous trip] and it was a 45 minute complete takeover. It was like Einstein's thought experiment. I rushed upstairs, wrote pages of notes, drew it all out, sent it to Dave. And he said, “You found it. You found the kinetic trap.”

Which is a chemist’s way of saying you found a system in which things get more complex ahead of their degradation. All of life still lives in a kinetic trap. This is why we don't dissolve in the shower, you know: water is trying to break us up and life and enzymes are putting us back together faster.

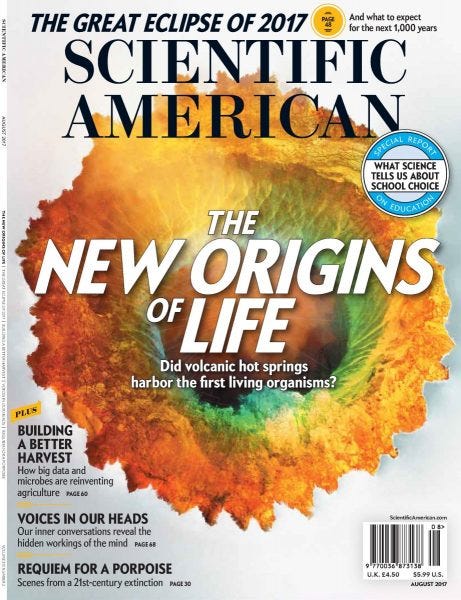

[Those theories] ended up in a publication in 2015 on the cover of Scientific American in 2017.

It was used by NASA to target the landing site for the next Mars Rover. I did presentations at meetings full of Rover people and mission planners. And then it rolled forward to 2020 when the full hypothesis was published in Astrobiology Journal. That's created a paradigm shift in our science [of the origins of life]. Out of the oceans from hydrothermal vents in the oceans, and onto land. There are maybe 20 teams working on this [today]. Every day there’s a citation of these papers. So a psychedelic-assisted innovation was able to land as a major new hypothesis in science in the 2020s.

This is one of the most extraordinary trip reports I’ve ever heard, and a testament to the creative power of the psychedelic experience. You can watch the whole interview for free immediately, as it’s one of a handful we’ve released before May 20th.

Another is the conversation I had with Laura Dawn, who has been researching the way in which the same mechanisms that help us heal from depression might be at play when our creativity is enhanced on psychedelics. In another fascinating interview, she describes people learning how to play an instrument with incredible speed and skill during a psychedelic experience, and other weird and wonderful creative phenomena.

Perspectivism and Indigenous Cosmologies

There is an aspect of Bruce’s story that touches on a theme I noticed in my conference interviews: the philosophical stance known as perspectivism. This constitutes the worldview held by many indigenous cultures who use psychedelics. It is touched on in our interview with Chief Mapu of the Huni Kuin tribe in Brazil, and with transpersonal psychologist Maria Islas, and with psychedelic philosopher Peter Sjosted-Hughes.

Perspectivism is the idea that to learn about something, say a tree, we have to become it. To use John Vervaeke’s terminology, we have to come into a perspectival and participatory knowing. Shamans understand animals not primarily by observing them as a subject observing an object, but by becoming a new subject. A deep relationality is built into this, and it is vastly different from the Western rationalist view that in order to understand something, we have to observe it from a distance in order to generate facts about it.

As a dyed-in-the-wool Integralist, I believe both are necessary for a full immersion in reality. However, perspectivism is sorely lacking in the West and often invalidated to our collective detriment. Damer’s story elegantly demonstrates why it needs to be included, and why multiple ways of knowing are needed for true insight. Damer spent years doing scientific research (gaining essential propositional knowledge), and then had an experience of becoming the research and actively participating in it.

This is a story I’ve come across often when studying the science of creativity; that the last step in true understanding is a qualitative shift; moving from ‘knowing that’, to knowing ‘what it’s like to be’ the subject you are studying, or the problem you’re trying to solve. It’s why public organisations in the UK sometimes invite ‘experts by experience’ into governance processes - people who have experienced depression or cancer or homelessness, to provide perspectives that doctors or social workers who haven’t simply don’t have access to.

Thinking about this, I’ve become convinced that any innovation process or creative endeavour should seek to marry objective study with perspectivism; one without the other will hinder our journey into new territory.

This was brought home for me interviewing another guest, Maria Islas. Islas runs a school of transpersonal psychology and indigenous wisdom traditions called Instituto Macuil. What struck me is that her journey to founding the school was inspired not by a psychedelic revelation, but through embodied practice. One day she happened to stumble across some indigenous women running a weaving workshop in a park in Mexico City. They invited her to join, and it was through the somatic experience of weaving that she connected with and began to understand their culture.

As Josh Schrei argues, somatics come first, and then culture. No practice, whether psychedelic or otherwise, exists in isolation of the body, or of its wider socio-political and environmental context. This brings to mind Nora Bateson’s work, and the piece she published here a few months ago.

The psychedelic experience, or the meditation experience, or the experience of falling in love, of watching a bird soar; these are all what Nora would call trans-contextual. They change meaning depending where you’re looking at them from. As such, instead of just talking about a ‘the psychedelic experience’ we should talk about psychedelic tapestries. Psychedelic worldviews that are embedded within the wider somatics and metaphysics of a culture.

And paradoxically, because paradoxes abound in this field, there is something essential to the experience that transcends time and place. That binds people together in union with one another and the cosmos.

Ayahuasca for Conflict Resolution

There is a long-standing debate around whether psychedelics can bring people together across political divides and toward a greater sense of unity. Rick Strassman, who ran the first study of the psychedelic renaissance investigating DMT, told me in his interview that psychedelics are ‘super-placebos’.

This is similar to Stanislav Grof’s idea that they are non-specific amplifiers: whatever is in your mind, or your soul, or your environment is amplified and intensified when you take a psychedelic. Nese Devenot and Brian Pace have argued that they are also ‘politically pluripotent’, meaning they enhance our existing politics. When hippies take psychedelics they connect with peace and love. Neo-nazis take psychedelics to connect to a pseudo-mythic purpose and deeper certainty in a racist worldview.

I believe this is largely accurate, but also overly reductionist, because psychedelics aren’t only non-specific amplifiers. They are also very specific, enhancing particular traits like cognitive flexibility, creativity and self-awareness across class and culture. The visions we experience, and the geometric imagery, is highly specific to the experience. So too is the way they change how we perceive the world; the loosening of boundaries, the connection to a deeper sense of reality, and the inversion of our ability to avoid pain, so that avoidance itself becomes the less desirable option than facing and accepting what we’ve been hiding from.

But can these ways of seeing and feeling actually lead to political change? This was one of the questions posed by an Israeli researcher (Leor Roseman) and a Palestinian peace activist (Sami Awad) who ran a ground-breaking study bringing together Israelis and Palestinians for ayahuasca ceremonies with the aim of conflict resolution.

Readers of my book will be familiar with this study as I describe it in Chapter 4. However, when I spoke to Leor about it for my book, he had just returned from the final ceremonies and had yet to publish the second part of what would become a two-part study. For the summit, I interviewed both Leor and Sami to find out what they learned.

Leor Roseman: The first study was more just ethnographic qualitative phenomenological research on the underground scene in Israel and Palestine, and not groups that we organized. We interviewed many Israelis and Palestinians who drink ayahuasca together. Natalie Ginsberg from MAPS also was involved in that.

The main themes that people shared when they're drinking in the space together, even without the intention of conflict resolution, was that there are powerful moments, [including] communitas, identity fusion, oneness beyond identities. But we felt we should be critical. Because [if only that is happening] it can normalize the [political] situation. It can harmonize the situation and deny the conflict from entering. Sometimes conflict is needed to process and to liberate from structural injustices and so on.

So we like the idea of ‘the irony of harmony’; that creating harmony on a small scale creates this pseudo-equality that prevents the kind of energy that is required, the anger that is required for changing real life inequality.

Sami Awad: Everything that came out of the first research paper, as Leor said, was done in a setting that wasn't organized with the intention of bringing together Palestinians and Israelis. So the question became, what if we do it actually with the clarity and the setting and the invitation for the participants to … engage in different aspects of conflict resolution, transformation, trauma healing tools, in addition to drinking medicine together?

We had three groups of Palestinians and Israelis. We met in Spain where we did this work.…there were beautiful moments where people were supporting each other, holding each other.

having different conversations with each other, going through processes together. [It was] a space of organized chaos, because we come from a chaotic place. So bringing that, but in a setting that is also held and clear, and a container that is able to hold that chaos, was very powerful and amazing.

Alexander Beiner: What was the most impactful thing you witnessed during a ceremony that has really stayed with you?

Sami: In the third group, we had a disproportionate number of participants; I think it was eight Palestinians and four Israelis. And no Israeli musicians as well. So all the musicians were Palestinian. And for me, it was beautiful during the ceremony how at one point, because the energy was also very Palestinian and very present, all of a sudden the music and the songs turned into something like a Palestinian wedding, a Palestinian celebration of dancing around the altar and singing Arabic songs and Arabic music.

At one point you could see the Israelis sitting on the side [looking uncomfortable]...one of the biggest traumas [for Israelis] is the demographic threat, that there is gonna be more of them than us, and what will they do?

And that came out. Stuff like this comes up in ceremonies. But in that dance, in that movement and the invitation, both communities mixed with each other, interacted with each other. The dancing started happening with everybody, everybody started participating and celebrating together. We could be one together. Our differences shouldn't be what separates us, but should be what brings us together to celebrate each other and our differences.”

Cultural healing and conflict resolution, with or without psychedelics, are more complex than holding hands and singing kumbaya together. As Leor and Sami point out, ‘we’re all one’ can easily mask political realities and dampen the necessary anger for change, and the revolutionary energy that can spark.

In Trish Blain’s (another guest at the summit) Four Forces model, this is an example of our desire for connection overriding our equally important desire for purpose and self-expression. DMT is the active ingredient in ayahuasca, and as I point out in my book, it is linked to prophetic, revolutionary experiences. The political becomes the spiritual, and the revolutionary energy of purpose penetrates the connected oneness to shake things up. Accordingly, a psychedelic approach to conflict resolution is wild, cathartic, messy, beautiful, divisive and unifying all at once. What would happen if we could bring this ‘all at onceness’ to conflict resolution and political polarisation more broadly?

Dropping In

The conversations I’ve touched on here are the tip of an iceberg crawling with geometric meaning. You can access all 40 interviews for free, and there are no hidden charges or sneaky requests for card details; you only pay if you decide you want access to the interviews after they’ve aired, but you’ll have access to all of the conversations on the week of the 20th and again on the replay weekend in June.

The summit also includes key figures like Rick Doblin, Rachel Yehuda, Paul Stamets, Robin Carhart-Harris, Erik Davis and Bia Labate discussing the latest research, anthropology, sociology, history and future of psychedelics. If you’re looking to break frame, learn a huge amount, and feel inspired, come along for the ride.

In the olden days we just took it and ran around in the woods or hung out and listened to music, etc.

Nothing scientific, no shamans from south America, just a quick trip to the Bronx and a Black Sabbath album 😂😂

Having pleasantly ingested acid, mescaline and mushrooms hundreds if not thousands of times in the last century I will say that although it was enjoyable and great for me, it is definitely not for everyone.

Will do have done I’m there see you there